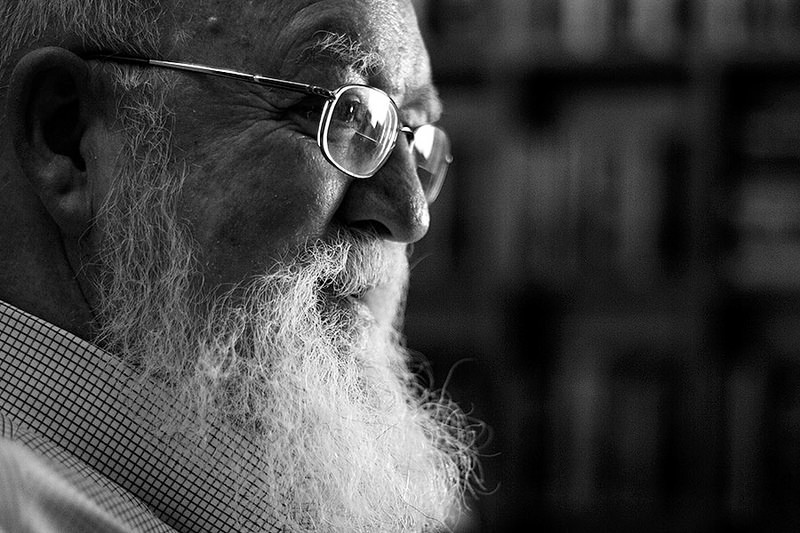

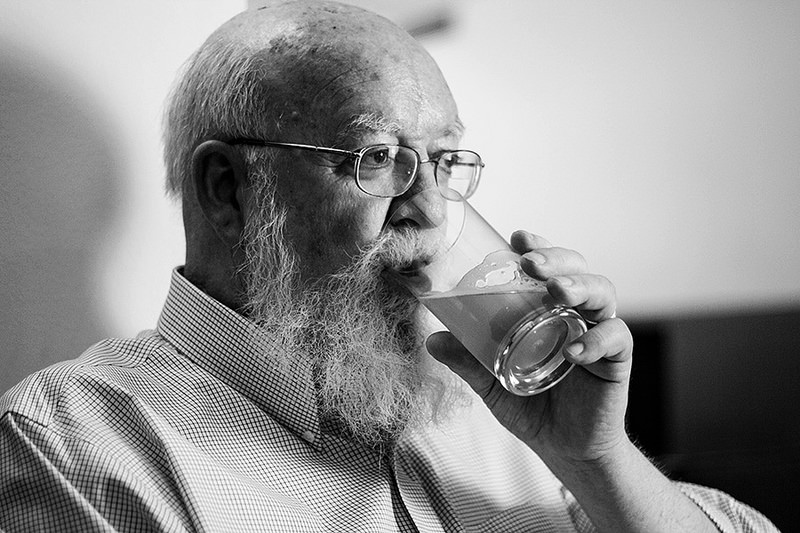

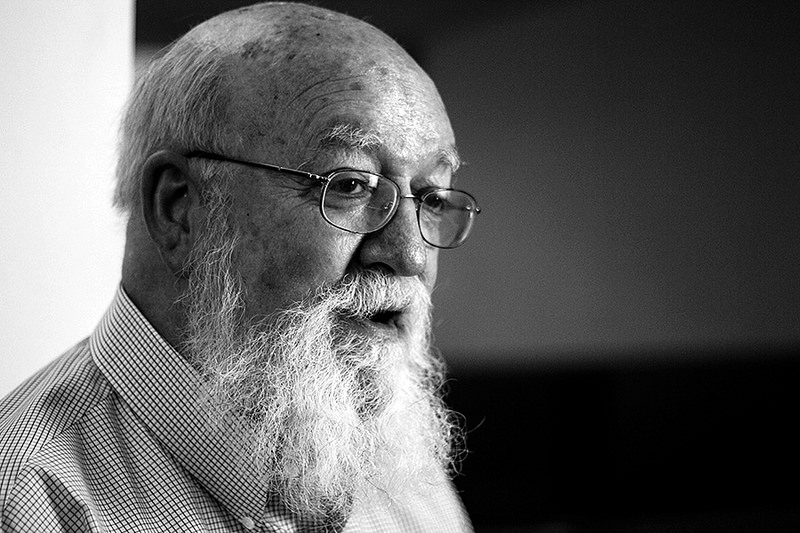

We meet Daniel Dennett (Boston, 1942) in the hall of the hotel in Barcelona where he is staying for tomorrow’s conference at CCCB, where he will speak about freedom and moral agents. This philosopher of science, renowned for his huge educational work, stands out because of his study of consciousness, intentionality, Darwinism and religion. Because of his thoughts about this last topic, he has been called, along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens, one of “The Four Horsemen of New Atheism”.

We talk calmly as Dennett sips his beer and thinks over his well-thought-out answers on science, religion, determinism, morale. We still have some time to dust off his rows with Steve Gould and even to chat about the latest movies on artificial intelligence. His evaluative silences prove that Dennett can bring out a deep reflection from any topic we mention.

Let’s start talking about freedom. Did Daniel Dennett freely decide to study Philosophy or he wasn’t a free agent in this choice?

I was a free agent. We don’t want our decisions to be at random. We want to have good reasons, and I had good reasons. Nobody coerced me, I wasn’t drunk at the time, I wasn’t under any terrible illusions, I wasn’t being obsessive… I just thought: “I think this is what I could be good at”. And that’s what free will is, it has nothing to do with determinism.

So, the influence of starting conditions is not in debate. To study Philosophy is your choice, but it also depends on your starting conditions.

Yes, we can’t get away from it, but it is not as bad as it sounds. One of the mistakes people make is that they think that just because we are caused by all the conditions we can’t control our destinations. In my first book on free will I had the example of the Viking spacecraft heading to Mars. When it got to a certain distance there was no possible way to control it from Houston, so they made it autonomous. Now it’s a self-controlling thing. They couldn’t control it, it had to control itself. We want to be self-controlled entities. And some people do it worse than others. And that’s what the real distinction is: those people who can control themselves and those who can’t. It has nothing to do with determinism.

In the autobiography that you wrote in Philosophy now you said that some of your friends were sons of eminent professors at Harvard or MIT, living in their shadows and striving to be worthy of their father’s attention. How did the absence of your father influence in your expectations and choices in those years?

A lot. If he lived, I would probably have been like my friends, desperately trying to live up to his approval and trying to be a historian as he was. And being a terrible historian. I just hope I would have had, though, the perspective to say “No, I’m not good at this, I’ll do something else.” I’ve seen too many children mesmerized by their father’s or mother’s expertise and fame. It’s hard!

So you were freer than them.

I was, yes.

After Harvard you went to Oxford to complete your PhD under the supervision of Gilbert Ryle. It is known that you have said in more than one occasion that he was a pillar of support for you, so it is funny to read your first opinions when you thought that you hadn’t learned any philosophy from him and compare them with when you discover this kind of osmosis of his indirect methods.

When I discovered that I was really ashamed, because I had been telling my friends that I wasn’t learning anything from that man. He was a sweetheart, but he wasn’t teaching me anything. And then, when I wrote the final draft of my dissertation and compared it to an earlier draft… he taught me a very great deal! But he did it so gently, with so little ego that I hadn’t even realized it. That was a really important moment to me because I realized that with a very good student you shouldn’t try to prove your side, just a few suggestions and let him or her go their way. If you’re right he’ll figure it out, and if you’re not you didn’t burden him with it. This approach to teaching is unfortunately rare in philosophy.

The other methods are more related to the ego.

Yes. When I first met Ryle I deliberately tried to pick fights with him, because it was funny. But it was terrible, it was like punching a pillow, he didn’t punch back, which I was so used to.

Regarding Ryle, do you feel more indebted to the man or to the philosopher?

That’s hard to say. people say, and I don’t disagree at all, that they see Ryle’s influence in my works, a conceptual influence. He was the last of the great ordinary language philosophers. You can see rylean methods running through a lot of my work, but at the same time I saw him avoid pissing contests among philosophers. He hated that stuff and had enough influence to intervene and distract people and get them to stop behaving that way, which I much admired.

You have helped to design museum exhibits for the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of Science in Boston, and the Computer Museum in Boston. What is your opinion about the debate on the future of museums?

I didn’t know there was a debate.

I mean, are they going to change or are they closer to disappear?

I hope not, museums are wonderful. Every kind: science museums, art museums… I love museums! I particularly love some of the weird ones. And I’ve been saying for years that the science museum that Jorge Wagensberg built here [CosmoCaixa, N del R.] is fantastic, unique. It’s one of my favourite museums of the world. I don’t know if it’s still the case, but last time I was there… No computers! No touchscreens! No simulations! Everything was real. That’s good. I don’t think any other science museum tries to live up to that standard. And maybe it’s outdated now, but it was fascinating to see how much you could do without computers. There were things you could touch, things you could manipulate… and that’s always important. A child can get lost in manipulating things, and that’s very good.

What’s it like to be a philosopher in the age of tweets and short attention span? Given the immense amounts of information they receive everyday, do you think the majority of people at your conferences and your readers are focused enough to really understand what you are talking about?

[Laughs] You have to start worrying, I think. For a number of years a very important part of my life was developing an instructional software, something called the Curricular Software Studio, at Tufts. I had the feeling that we were making it too easy for the students. It can make it hard for teachers when the students now expect bleeps and flash and everything very fast and crystal-clear. At some point they should have some serious experience of dredging, of hard-boring-disciplined work. Otherwise, they won’t be any good. We have to make sure we don’t make it all so much fun that people forget that there is some hard work to do. Some of my heroes in science are people who spend years and years and years looking at shells or birds, counting bird calls… it’s unglamorous work and they do it with dedication. Everybody depends on them to do the data-gathering right and have to spend some time in the field. And though it can be tedious and tiring, I hope it doesn’t disappear.

Let’s talk about your work. As with many others, trying to catch up with a popular audience has, in some terms, undermined your credibility in some circles, mostly academic. Are these critics defending a kind of intellectual class war where popular science or philosophy are seen only for their elite?

I decided long ago that it was a price I was prepared to pay. Somewhere I read that a very distinguished philosopher walked out of my lecture in Oxford saying that he was damned if he was going to learn anything from me. And, truth to be told, he never learned anything from me. And I know that in some philosophical quarters I’m written off, I don’t think I am in the scientific ones. Or maybe I am and they are keeping it from me. But I know that a lot of philosophers put down their noses at what I do because I use diagrams and pictures, I’m on television a lot… Ok, I wouldn’t trade places with them for anything. Somebody could do a study about this: in a field like Philosophy the best thinkers get established as the best thinkers, and then they have to teach grad students and their fellow partners. They become less and less confronted with the task of explaining it to undergraduates. And, when that happens… death. Because the graduate students will walk on when they don’t understand, they’ll fake it. The undergrads will say that they don’t understand and then you have to explain it. Most of my ideas come from being confronted by an undergrad student and his enthusiasm to ask me questions. Grad students are too scared to ask these questions. They won’t admit that they don’t understand it. I won’t name names, but I see books which have been written for the eyes of six people in the world, they don’t expect anybody else to read it and nobody else is going to read it. Probably being read by anybody else isn’t worth.

Could you explain us a little bit about what was what you defended that moved some people to refer to you in offensive terms such as ultra-darwinist or Darwinian fundamentalist?

That was Steve Gould, of course, who was an artist of propaganda. It was a brilliant term which he used quite effectively for a few years. The story of my interactions with Steve Gould is a long one. There was a time when we were friends, when I went to his seminar and when he came and spoke to my seminar at Tufts. But then I began to see him deliberately misrepresenting a lot of work in the field for his own agenda, and I began to call him on that, privately. He just told me that he was right, I was wrong and that was it. When I wrote Darwin’s dangerous idea I had that whole chapter about him. I had been encountering really serious problems, people who couldn’t get jobs because they were in a field called sociobiology. They weren’t working on people, they were working on ants, prairie wolves or something, but still they couldn’t get jobs because they were sociobiologists and Gould had shown that sociobiology was evil and politically wrong. But he had his agenda. So I thought that when I speak about evolution I would put a chapter about Gould. We had many mutual friends, and one of them looked at that chapter on draft and asked me not to publish it. I asked if he said it because what the chapter said wasn’t true, and he said that was not the reason, but that Steve would get very hurt and would destroy me. I asked him if he could promise me that if I left the chapter out he would convince Steve not to badmouth my book and tear it to shreds. Of course not. So that’s why the chapter had to be there, it would be lame if I published the chapter later. For two years if asked a journalist for his opinion on my book he said it was beneath mentioning, he wouldn’t talk about it. But then Maynard Smith, the dean of evolutionary biology wrote a lovely review in the New York Review of Books and in his review specifically said that among his colleagues Gould’s thinking was too confused. And then Gould just went ballistic. And that’s when he published those two pieces. He was very hurt by Maynard Smith’s review. People said that he would destroy me… and no, he didn’t. It was not entirely pleasant, but I was not suffering. If you want to read how terrible I am you can read that book, The structure of evolutionary theory.

It was more a personal disagreement than a philosophical one.

I was just one of his targets in that book. But he certainly saved some of his venom for that last book.

Let’s talk about religion. Some people call you, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens the “Four Horsemen of New Atheism”. If I were you, I would make some t-shirts with that slogan.

I think people have, but I don’t have one yet.

Good times for the atheism?

Yes, it is. Very good times. Richard Dawkins, after the publication of his book, began collecting advertisements for books attacking our books and, mainly, his book, The God delusion. In the second volume of his autobiography he’s got a huge array of books, dozens of books, that were published attacking us. It led me to a project which has taken a lot of time but I’m glad I did it. The project with Linda LaScola.

What’s that project?

Linda is a trained psychologist and she approached me with the idea of finding closeted atheist clergy. Pastors, ministers, priests who still have a church and a pulpit but they’ve lost their faith. We did find them. Dozens, actually. And dozens agreed to be interviewed in deepest confidence by her. And their stories are very moving. First we published a short article about the first five that we found, and we were very sympathetic to them. And then happened just exactly what we wanted to happen: we got a lot of people getting in touch with us saying “Those were five good stories, but do you want to hear mine? I’ve got an even better one.” Then we had more volunteers than we could handle. I got another twenty grand from a Canadian benefactor to cover Linda’s expenses, because she’s doing all the interviewing and travelling. So we put it all together in a book called Caught in the pulpit. It was published by Amazon as a print-on-demand paperback, but that way we were not getting any reviews. But this last month from Pitchstone Publishing we got a second and expanded edition. And if that wasn’t enough… should I tell you this? I don’t know whether I should, but I’m so enthusiastic I have to. On the 28th of this month [This interview was made in mid-May] I’ll fly down to New York City and we’ve commissioned a play done entirely from the transcripts and is having a first reading in Manhattan by some very good actors, and some important theatre people from New York are going to be there. I think it’s gonna be a very fine play, because those people are so real and such good people who got themselves in such bad fixes that’s it’s like a confessional, except it’s not with a priest, it’s with Linda. It’s a secret they haven’t told anybody: their spouse, their kids. We’re hoping that the new edition sells better and gets more noticed, but now I’m also hoping that the play can be a real eye-opener for a lot of people, especially since everything in it is just as it was spoken.

Are you planning to have that play somewhere in the Bible belt?

That’s what I dream of. Of course I’d love to see it on Broadway and on television, but it’s a play that is very easy to stage because it’s just Linda in various motel rooms talking to various people. So you can do it only with a few actors. It would be lovely if it became a play that high schools wanted to perform. Many high schools have an annual musical comedy and a serious play. And it would be hard to school boards to say they couldn’t do it, because it’s real, there’s no sex or violence.

Do you often travel South to the Bible belt?

No, I don’t. Chris Hitchens did. When my book Breaking the spell came out in 2006 I did a book tour and the publisher and the agent thought that it was not wise to go to the Bible belt. I was told by various presumably wise people that my life was going to be in danger, that I had to make sure I had bodyguards and police, my wife was scared… And Hitch just went all over the South, all through the Bible belt to huge audiences, everywhere he went. What’s interesting is that that’s the state of mind of America at that time. Religious rightness was becoming so aggressive and arrogant… that’s 2006.

Intuitively, because of our need for ethics to rely on a bigger purpose, most people are afraid of the idea of the immortal soul not being real. Yet you embrace it.

We certainly don’t have an immortal soul. You don’t have a ghost in your spleen or in your heart, we don’t have an immortal soul. We do have a soul. I had an interview with Giulio Giorello in Milano and the headline in Il corriere della sera the next day was: “Sì, abbiamo un’anima. Ma è fatta di tanti piccoli robot.” Yes, we have a soul, but it’s made of lots of tiny robots! And that’s exactly right, we’ve got a software soul, which distinguishes our brain from the brain of a chimpanzee or a whale. Our brain has hundreds of layers of software and gives us free will, gives us more responsibility. Software is just information, and that’s what our souls are.

Despite being an atheist, you still read the Bible.

Not on a regular basis, but I’ve read lots of it and I can usually find a quotation.

Is it the greatest fantasy book ever written?

I don’t like fantasy. I don’t like The hobbit, for example. I don’t know why, but I really don’t go for all of that stuff. So I have not aesthetic standard of what great fantasy is. I think the King James’s version of the Bible is great poetry. I grew up with it and I love it, but it is also full of weird and terrible stories.

I have read that you love sailing. If you ever get caught in a storm while sailing far from the coast, won’t you say “C’mon, God, you and me know you don’t exist, but just in case…”?

No, I wouldn’t… I mean, I don’t know, I think I wouldn’t. I would be so disappointed in myself… [Laughs]

You go walking around your city and someone comes at you and tells you that you should know Christ. Most people think it’s irritating but normal. Why would it be very weird if it was an atheist who told you you shouldn’t believe in God? There’s no preaching for atheism.

In the United States most people don’t talk about believing in God -I’m not sure about other places- until the right wing, religious people, began to be obnoxious and scary. But we’re polite, we don’t feel any urge to go around spreading atheism. What woke me up was that Richard Dawkins -old friend- sent me a copy of the review, the op-ed, that he had written for The guardian on the Brights. It was the first time I heard about this Brights thing. I read it and just happened that the next day I was heading out to Seattle to a special meeting of intelligent and smart high-school kids from all over the country, who gathered in Seattle to be talked to by a bunch of overachievers: scientists, philosophers, novelists, architects, dancers, painters. Each of us had only fifteen minutes to tell these kids about ourselves. I was one of the first ones, and just as I got up on the stage i thought I was going to do an experiment. I said I was a Bright, and explained what a Bright was. And afterwards I was mobbed by these high-school kids. So many of them who told me that they thought they were alone, they didn’t know that grown-ups or anyone thought that way. That really made an impact on me. And it also made an impact in other speakers at that conference, because maybe ten of them did their talking and ended it saying they were also Brights. Then I wrote my piece on the Brights for The New York times. It was summer, a July, and it was the most downloaded piece of the month. I was flooded with mail from people telling me not to stop there, I had started something and had to do something. But I didn’t want to write a book about the atheism but I thought about using what I had been working on anyway, about cultural evolution, to write a book about religion.

Are you an atheist because you are a scientist/philosopher? Are you a scientist/philosopher because you are an atheist or are they non-related facts?

I’m sure it’s related, but I don’t think that one is the cause for the other. Most scientists are atheists, most philosophers are atheists. The question is there is a sizeable contingent of religious philosophers in the United States, but they are not a majority. They sometimes complain that they are the downtrodden minority in Philosophy, they are the ones who have to hide their religious faith for not being ridiculed. And I think there is truth in that. It’s hard for religious philosophers to get respect from who are themself non-religious philosophers.

How can you explain that someone is able to be studying the Big bang and, at the same time, believe that God created the world in seven days?

The defining center of philosophy is epistemology, especially in analytic anglophone philosophy. Reasons, references, arguments and science are major topics. And that background of systematic skepticism is an ambience that isn’t very friendly to propositions which on the face of it look preposterous. Philosophers who are religious often have to work very hard to carve out a little of epistemological room for them to operate in, and they do it with various degrees of plausibility.

When you came to Spain in 2012, you said in an interview that football (soccer) was like a soft religion. I understand this idea of connecting people without exclusion, but at the end we have the same problems as religions. There are mild believers and there are fanatics that totally forget the principles of their communities.

I don’t know if it is as bad in Spain as it is in England, but I’ve seen it and it’s ugly. And indeed, religion doesn’t have a monopoly on ugly fanatics. There’s a problem that is going to get worse. The modern world is going to be providing two things which are explosive: less thrilling life opportunities and huge exposure to the few that do get to have the thrilling jobs. It’s an old problem. I like to quote the WWI popular song in America: “How are you going to keep them down in the farm after they’ve seen Paris?” That was in 1917, and whoever wrote that song saw that the men who experienced war in the trenches of Europe were not going to be very happy as farmers. You don’t have to experience war directly, the movies can show to you the superheroes. I wonder, if you are a young man growing up in some unexciting part of the world and you look at your future and all you see is running a corner petrol station… boy, almost anything will look better than that. And if you hear promises of glory you will go for it. You can hardly blame them. Partly because of the glorification of these lives that they get to see. So I’m beginning to try to think more about how to create organizations and movements that maybe will not solve the problems that need to be solved in the world, but that can provide the joy of community in fighting the good fight. I really think that would be important. And it can’t be the boy-scouts, it has to be something more adult and exciting than that.

Charlie Hebdo’s new director decided that he won’t be drawing Muhammad again. It is a wise move?

I want to go back to the Danish cartoons, we missed a great opportunity there. Every newspaper and television station in the world should have shown those cartoons and just said as firmly as possible: “Don’t be children, grow up. You do not have the right to demand this.” Most muslims would have been so grateful if we had done that! Instead, we missed that opportunity and we gave a great boost to the fanatical elements in islam. It was a huge mistake. If we had held the line higher then, we might have turned the tide.

And what’s the right thing to do nowadays? To survive or to try to be a hero for the freedom of speech? It’s a hard choice.

It is a hard choice. I have islamic friends and I ask them how can I help. And the say: “Don’t get near us.” [Laughs] That’s so depressing… But I have some optimism about this. I did a piece with Deb Roy in the Scientific American in March. We argued that same as the Cambrian explosion of 540 million years ago, which was caused by the ocean becoming much more transparent, so eyes evolved and every species of animal in the ocean was challenged and a lot went extinct, the new electronic media, social media and cell phones have changed the epistemological atmosphere of the planet and every organisation in the world -armies, churches, corporations, universities, governments, the CIA- is becoming transparent and it can be affected by its transparency. There’s going to be a lot of Snowden and Assange, and it’s going to shake up everything. So when you apply this to islam it looks to me that we ought to be able to arrange it with gentle provision so that young women and girls in the muslim world are provided with material that is not anti-islam, it just opens their eyes to all kinds of things in the world. And either muslims are going to deny them any cell phone and internet or they are going to have to make an accommodation and start letting girls and young women get educated, properly. And if that happens islam will be transformed in a decade, for the better. It won’t be without violence. Being cynical about it, islam will make some horrific public relations mistakes and the world will express such disapproval and contempt that they’ll have to change.

Can we erase fanaticism or where there is a religion there will always be some fanatics?

There’s roughly a 30% of people who have no taste for religion at all. One of our closeted clergy taught us a wonderful word for these people: they are ignostics. They just ignore it, they don’t care, it’s not even worth being agnostic. So 30% of people are ignostics, they just aren’t turned on by religion at all, it doesn’t matter to them. And then there’s like a 2% to 5% who are like people who shouldn’t drink because they can’t handle their liquor. In my lifetime we had a real attitude switch in America towards drunk-driving. When I was a kid people used to excuse drunk-drivers saying: “Poor guy, he was drunk, he didn’t know what he was doing.” Now it’s the other way round. They are responsible because they got themselves into that state. And, most important, their hosts and the bartenders are legally responsible. There’s party-givers who let somebody drive drunk and that person killed somebody and they are in deep trouble. And I think that’s good. If only we could arrange for religious leaders who foment religious intoxication to be held responsible we’d be making some progress.

I have to say I was shocked when I read that you don’t like the term Theory of Mind and prefer the phrase The Intentional Stance.

Well, it’s my phrase, why wouldn’t I?

You don’t like the name or the concept lying behind it?

Intellectualizes a competence. To call it a theory suggests that there are theorems and it is a very rational and evidence-using. But I don’t think it is a theory, it’s a talent. It’s partly instinctual and we don’t have instinctual theories. Folk physics is a very interesting field. My friend Pat Hayes wrote the Naive physics manifesto. Naive physics is the physics you don’t learn at school, it’s the physics that you learn by just growing up. You know you can’t push a chain, you can pull it. Or my favourite example of folk physics: if I were to tip this glass of beer you would jump back, but if there was a big fluffy towel there you probably wouldn’t, you would expect the towel to absorb the liquid. That’s folk physics. It gets us through life pretty well, it keeps us from walking into a wall. And there are no theorems. What’s cool about folk physics is that there are things that folk physics say they can’t work, like gyroscopes, siphons, pipettes, sailing upwind… but they do. Discovering the failures of prediction of folk physics is what creates science. And there’s the same thing in psychology, we have folk psychology, and it’s not a theory. Folk psychology is just like folk physics: it’s a talent of expectation that you get and use.

In our current economical system, funding science clashes with the idea that investment is where the business is. An example is in the big pharma, where rare diseases have to fight with those diseases that have much more prevalence. How can we defend and protect this other kind of research that hasn’t got a direct return of investment, as humanities or philosophy?

Big pharma has a lot to answer for on that. Someone who is making a huge difference in this way is Bill and Melinda Gates. They are pouring billions of dollars into those diseases that are not the diseases of the rich. And scientifically are not as glamorous, like malaria and all the other African diseases. And that’s wonderful.

But then we are relying in some persons to do it.

Well but, you know, people want to be good. Incredibly, they really do. We have to find opportunities for them to do that.

Making it easy for them to be good.

Make it attractive. This reminds me something I’ve been talking about in Girona last week: people I know in the world of the internet think that it could go down. Some of them think it’s inevitable, and I mean really go down, really crash, the whole thing. If it went down in America it would probably take down the power grid with it and the cell phones for sure. And the networks. And the radio stations. And America would be plunged into an electronic blackness. Think what would happen in the first five hours: panic like you would not believe. So I’ve been worried about panic in an event like this and how we could forestall panic. I gave a talk on TED about this two years ago, but they haven’t put it in the air yet, I’m not quite sure why. Not my best talk, but still. Danny Hillis has a talk in TED called Plan B, which I highly recommend. It turned out we both were worried about the same thing. He has the technical fix, he is trying to get a second dedicated internet shield for vital services. He says is not that expensive, and he has talked to the White house and the Congress, but Congress makes a big mess about this. He is looking for help from the insurance companies and the banks because they’ve got a lot at stake in this. So that’s their plan B. I’m working on plan C: what to do if he doesn’t get that up and running before it happens. And I figured out that what we need is a bottom-up self-organisation, we need about 300,000 “lifeboats” scattered around a thousand people max for each to build a community organization. It can be a library, a school, a pub or a church. I think churches would be very good at this. My real dream is that this would be a wonderful way of repurposing a lot of churches, because this is just the sort of thing they would be good at. You put together local citizens and you don’t need hi-tech. In fact, lo-tech is good. If they know how to fix a generator, how to make a steam engine run on firewood… All I really want to do is to create 48 hours of relative calm so the people wouldn’t freak out immediately, because fearing the worst, I think people would be ready to loot and kill, and we have 48 hours of grace period to get the technicians a chance to get it up and running again. That would probably be enough, because if it lasts longer than that people would have been in contact with each other and their worst fears would be probably alleviated and they would be ready to think about what they can do. I want to put a meme in their heads because I don’t want them to panic and not know what to do. I want them to think about those neighbours who mentioned that they were setting something up in that cornershop in case this happened. Meanwhile, the people who are volunteering to do this would have been talking to the radio operators, they’ll have their minigraph machines printing posters to put on the bulletin boards, kids on bicycles ready to take copies of this around, they will know where water is, where food is, who needs medicine, who are the pharmacists, how to get in touch with them. The point is that after all, if this happens, we are only going back to the 19th century. And people could live very comfortably in the 19th century without all of this stuff. So the transition could be very peaceful, but only if people don’t freak out. That’s my plan for churches: panic absorbers.

As a philosopher do you think there are any limits for knowledge and research? Can science go too far on its investigations?

Yes, we have to look at the environmental impact that divulging a knowledge will have. And I don’t think it’s hard to imagine cases when information was better off not knowing.

To what extent is dangerous the fact that people apply the ideas of scientific determinism to their daily acts? Something like ‘It’s not my fault, I was predisposed to do this’.

I think that’s a fundamental confusion. It is maybe the only time in my career when I think I can look to some of the scientists I know very well and tell them they should go back to school and learn some philosophy because they are making philosophical mistakes and really underestimating the problems that they think they are solving. Somebody, and I won’t say who, recently published a book called My brain made me do it. And I thought that is what we all want, who else would you want to rule your actions? But, you know, that wasn’t really the point that the guy was trying to make.

What is the idea behind a philosophical zombie and why is it impossible from your point of view?

I think it’s such an obvious failure of imagination… They are sure they can imagine a zombie, and I say that they can’t. Here’s a bad argument: I can imagine an entity which is atom for atom indistinguishable from an alive cat. But it’s not alive. Does the fact that I can imagine it make it true? No, it doesn’t show anything. Whatever exercise of imagination I went through doesn’t count for much. What do you think you are claiming when you say that zombies are conceivable? What’s the test for conceivability? It’s amazing that philosophers in the 21st century can talk about of the conceivability of zombies as obvious and have not addressed the question of how you tell whether they are conceivable. They call it a revolution in Physics because they can conceive of a zombie. Well, I call for a revolution in Biology because I can conceive of a non-living thing which moves and acts just like a cat.

You defend free will. Can we really have a free will within a society? Doesn’t your background matter?

We are all affected and constrained by our upbringing. Not any of us is as free as he’d like to be, but we are free enough. And not all of us are. What really matters is that we have laws. But there are laws that nobody can respect, and having them is worse than no laws at all. If you have a law the enforcement of which most people would not respect you have to make an adjustment. And that’s a sociopolitical fact, not a metaphysical fact. We know your brain makes you do it whether you’re Einstein or a psychopath. Now the question is how did the brain make you do it. We want to look at cases, we want to know whether or not you had enough free will, whether or not you were enough in control on the occasion. And some people don’t. As we learn, with better and better tests, we will discover that some people that in the past we would have held responsible we now say they have diminished responsibility or no responsibility at all. We’ve done that in the past, and we are not throwing away the concept of free will and responsibility, we’re just adjusting the boundaries as we learn more about which side of the boundary some types of cases fall. In 1984 I made a claim, that the developmental process that brings us to adulthood is a long process and we may have started on the wrong foot, we may have had a deprived childhood, but it’s like a marathon. Some runners start 50 yards behind other runners, but the luck is over after 26 miles, that’s not unfair. And the same for your chances in life. You are going to have some afflictions, some setbacks, some problems, maybe you had a terrible childhood. But does that mean that you are never going to be responsible? Maybe, but not because you had a terrible childhood. Bruce Waller didn’t like this and said that there is too many cases where it’s clear that the odds don’t average out, and if you look statistically at the children who have blighted childhoods, abusive drunken parents and the rest of that and you compare them with the children who have this charm-life childhoods with intelligent and loving parents you see that the richer get richer and the poor get poorer. But I don’t think there is an evidence for that. Suppose you look at a million children that have had very bad childhoods and you see that, indeed, 250,000 of them get in trouble. That shows that 750,000 didn’t. And we have to remember also that there are people who start with charmed lives and end up doing bad things. We should be ready to adjust our laws as we get the scientific evidence that shows which people can be held responsible. People want to be held responsible because it gives them the chance to live free lives in society. I use an example: suppose I’m pulled over for speeding and I tell the arresting officer that I’m a philosopher, I’m absent-minded and I couldn’t do otherwise, I was lost in thought. He would tell me that I’m incompetent to drive and he would take my driving license. But I want the freedom of the highway, so I’ll take my punishment, thank you. I will accept responsibility gladly so that I can go out and keep driving. The benefits of being a free citizen are high, so people want to be held responsible.

Do you think the idea of consciousness has been always morphing to continue allowing positions like dualism or that someday in the future we will finally say “Ok, that’s it. Everything is explained and nothing allows this idea of immateriality”?

I’m such an optimist that I think that dualism will look as quaint as vitalism looks now. I don’t think anybody takes vitalism seriously. Well, no, that’s not true, there are some crackpots. I think we’ll complete the project I started with my outrageous title: Consciousness explained.

If I have to be honest, when I heard David Chalmer’s idea of the Hard Problem of Consciousness I couldn’t agree with his conclusions because they sounded to me very mystical and far from science. Am I wrong?

No, I don’t think you are wrong. In fact, on Edge this year the question was: Which idea should we extinguish, which scientific idea is past its sell-by date? And I said the Hard problem. It was not a scientific idea, but it was fooling scientists. David Chalmers and I are on good terms, but we don’t agree.

So, being very (very) reductionist, it is something about feeling more or less optimistic in our expectations of bridging the gap between mind and brain. And Chalmers is not very optimistic.

David is a very smart guy, he is not anti-science, not a fool, he has this grand intuition. He just decided he is going to rule it and one time, when we were discussing this, I tried another argument, and he said to me: “Don’t even try. That’s just an intuition of mine, and your arguments are never going to budge that”. I asked him if he had considered a change of diet, and he was angry with that. Hey, he told me not to try with arguments, what else could break the spell? Well, maybe long hikes and cold showers, I don’t know.

This Chalmers’s “I’m not going to change my opinion” is not a very scientific position.

It isn’t. We had this workshop up along the coast in Greenland in June, organised by me and sponsored Dmitry Volkov. Chalmers was there with two colleagues, and we had wonderful conversations for a week, and I came away not the least persuaded, but understood him a lot better, although I don’t find any wisdom in that.

Let’s talk about the self. Imagine that I have a neuroprosthesis that I feel and looks as real as my own arm. Could I say this implant is a part of mine?

See what a blind man can do with his cane. He can feel different textures: wood, leather, glass… he’ll tell you. And he is feeling it out of the tip of his cane. It’s an extension of his sensory body. And when you drive a car you can feel a grease spot on the road when the car slips a little bit.

Then, which are the limits of the self?

People who work in nuclear fuel plants have these hand-things they control by watching them in a screen, and they certainly feel they are in the room there.

And could a hypothetical robot in the future have a sense of self, a consciousness, too?

Unbelievably hard to do it, but in principle yes. In the film Her, at the end, he knows he is not the only one she is taking care of, there are hundreds of thousand more. That’s the great unmasking because then you know that of the two in principle possible ways of doing it she is doing it according to the second one. If you go back to the Turing test, remember Turing compared it with a power game where there a was a man and a woman doing the typing behind the screen. The woman just was a woman, and the man pretended to be a woman. He could answer questions that would convince a proving judge that he was the woman. That would be pretty impressive. But notice, it doesn’t mean having the psychology of a woman, it means having a theory about the psychology of a woman that is so good that you can fake it. What we learnt at that moment is that she has a theory about what the ideal female companion to this guy should be, so she is doing it the second way. She might even be doing it following a real psychology, but then she would be conscious like us. If she’s doing it the second way it’s a different sort of thing. She’s going to have to be conscious in a very unusual way, but not like us.

You just mentioned Her, but If I am not wrong, your favourite film about artificial intelligence used to be Short Circuit. Has Her taken that first place?

Short circuit was much earlier, and it had some virtuoso touches that an extremely non-humanoid robot was nonetheless very affecting. Making something that insectoid that lovable was just a very clever movie start, very well done. Her has other properties, and it has Scarlett Johansson. [Laughs] There’s a movie I haven’t seen, but I heard good things about: Ex machina. I think I’m going to like that film. But there are also bad movies. A.I. was a bad movie.

And the last question, also related with robots. Have you found more information about Tati, the antique robotic dog that you bought in Paris?

A History of technology scholar at Harvard did a dissertation on early French robotics. He heard about Tati, came over and took hundreds of detailed pictures of it. He then investigated all the parts, and pretty soon I was getting emails from him saying that the solenoid in such and such place was manufactured by Philips in Belgium from 1954 to 1959. He was trying to work out what place the parts came from. But we still don’t know for sure who made it. There was a funny incident some years ago. Out of the blue I got an email supposed to be from Sophie Duez, a French movie actress, very well-known, very beautiful and very sexy. I didn’t know who this was, but she said she thought she knew where my robot comes from. It was commissioned by prince Louis de Broglie, the Belgian Nobel-laureate physicist, for his granddaughter. She fell on hard times in Paris and sold it to the antique store where I bought it. Well, wonderful story. I don’t know if it’s true. I wrote back saying that I would happily give her the reward if she gave me any corroborating evidence. She replied that she didn’t want any reward but she was working on it, just to let her get the evidence together. I said I would be patient, and announced that I was going to Paris shortly, so she would be able to tell me anything she had found. Then I got some evasive emails, but including attached some nude pictures of Sophie Duez. I checked on the web and sure enough this was Sophie Duez. I showed them to my Parisian friends and they got quite excited about this. And I know that in every one of my lectures some of my friends are looking around, but she never showed up. And if she did she was in some completely disguising costume. And then all the communications dropped. She sent me half a dozen naked pictures and that was it. I think it was somebody pretending to be her, I don’t think it was her. It was my little Her.

Pingback: Daniel Dennett: «Es complicado para los filósofos creyentes ser respetados por los filósofos ateos» - Jot Down Cultural Magazine

Gracias por publicar las versiones en inglés y en español, y por dar tiempo y espacio al entrevistado, en este caso totalmente merecedor de atención. Sois uno de los pocos medios que de verdad aprovecha las ventajas de publicar en internet.

Pingback: Las dos caras de la filosofía contemporánea