French/English Interpreter: Brian Valente-Quinn. Wolof/French Translator: Babacar Thiaw

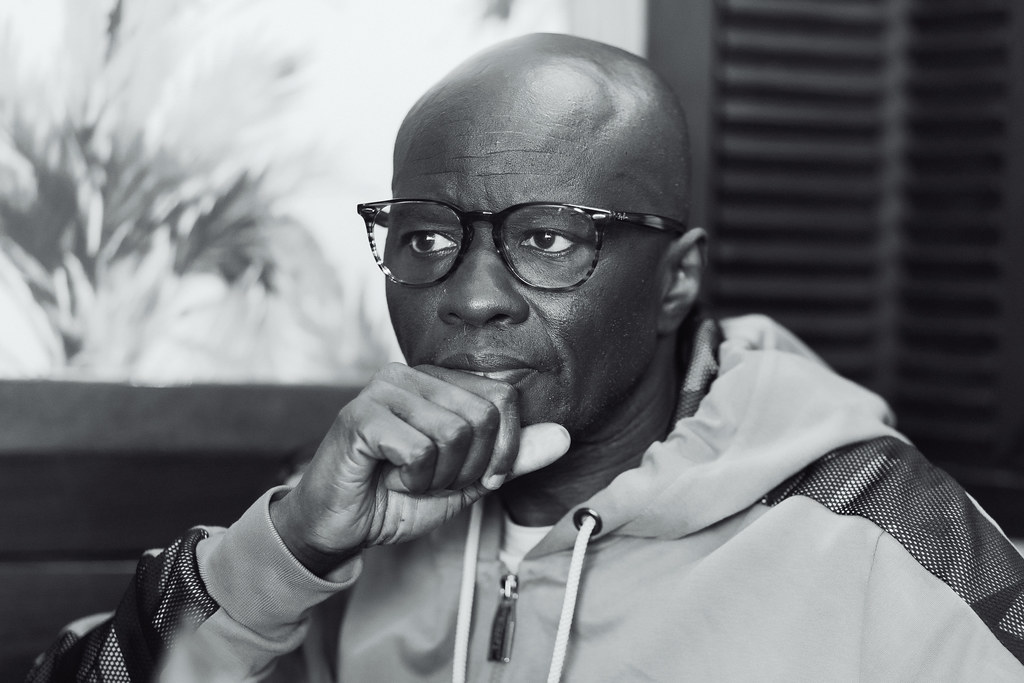

Omar Pene, co-founder and lead singer of the Dakar-based supergroup Super Dianomo, has been composing and playing for 50 years, releasing albums both with Dianomo and as a solo artist. The style he helped invent fuses traditional Wolof percussion, multi-ethnic religious music, soul and blues styles into «Mbalax,» a genre that dialogued with Cuban music and eventually supplanted it as the dominant pop music in Senegal in the years after that country’s independence. A long-time advocate of Pan-Africanism, his contributions have been recognized by ECOWAS (the Economic Community of West African States). Pene has been sounding the alarm on climate change and the increasing desertification of Senegal for years, and he released the thematic album «Climat» in 2019. Pene is also a Goodwill Ambassador to Students on behalf of President Macky Sall’s government.

Shall we talk about mbalax music, Wolof music, Senegalese music, African music, West African music, or just music?

We can simply talk about music.

How important is the Wolof identity in your life and in your music?

I am Senegalese, I was born Wolof; it is my mother tongue. That’s why it’s such an important tradition for me, because it’s a value that we want to transmit. Because the English sing in English, the French sing in French and the Wolof sing in Wolof.

How did you start your musical career?

I started when I was very young, but not in an orchestra. I sang in the street with friends, for fun, because I really wanted to have a career as a soccer player. I became a singer by chance. A man who lived in my neighborhood and was part of a group called «Le Kad Orchestra» heard me singing like that in the street, and he asked me to join his group, and of course I wanted to…. I had a voice, even though I’m not a griot, because usually it’s the griots who sing. At that time, I wasn’t interested. I wanted to play soccer, period. But my friends asked me to go try out, because there were a lot of soccer players in the neighborhood, but no musicians.

I’ll tell you an anecdote that is quite humorous to me: One day, I was coming back from training – we were playing soccer – and I showed up at the place where the band I wanted to join was rehearsing. As soon as I showed up in my soccer gear, the director wanted to throw me out. But the man who discovered me said, «Oh no, it’s that guy I told you about. I’ve heard him sing, he has a [nice] voice, so we can try him out. I did the audition and they said, “Yes, we’ll see him again.” A week or two later, the man came back to tell me: we have decided to accept you in the group because we need a young singer who can sing in Wolof.

The m’balax that exists today did not exist then, because the orchestras played more Latin music, more salsa, and sang a little in Spanish.

So I joined the group and that was it. That was in 1972.

How old were you then?

I was 17 years old.

Was the decision to sing in Wolof that director’s decision?

Yes, because at that time there was an awareness that people wanted to get a little closer to what we were culturally, in terms of identity. Because music from other places was popular, music imported from Latin America, salsa. We didn’t even use traditional instruments like the sabar, the xalam or the kora, instruments closer to our identity.

This lack of traditional techniques in the popular scene: Was this the case in rural areas as well as in cities?

Yes, of course. In fact, there was a much more traditional music called folklore that was sung by the old griots. At that time, that music was much more common in the villages, but it wasn’t danced to. When you went to a club where a group was playing, it was more Latin music.

Now we needed to get a little bit closer to our cultural identity. Leopold Sedar Senghor, who was then President of Senegal, was a man of culture. He wondered why Senegalese groups did not play music closer to our culture.

Because music is rhythm. Senegal is made up of many ethnic groups and each ethnic group has its own rhythmic culture. In the population of Senegal there are the Wolof, of course, but there are also the toucouleurs, the sérères, and the diolas in the different regions, and each ethnic group has a rhythm and a beat that is also danceable. Why not try to move towards that to find our true identity?

If these traditions had vanished, how did you manage to find them?

That’s a very good question. I think it was a generational reflection, once again. That’s where the idea of creating [Super] Diamono came from. At that time, we weren’t very interested in Latin music. We were more interested in Anglo-Saxon music: jazz, rhythm & blues, reggae, soul.

James Brown?

Yes, James Brown, Otis Redding, Bob Marley. We thought that was much closer to our traditions because it was much more «black». At that time, we had very revolutionary ideas. We were more on the side of the great men of Africa: Nkrumah, Nelson Mandela and the others. We were a little bit further from what was being done at that time in terms of music, especially because we had done a little bit of research on philosophy. From the beginning we decided to include an instrument called the sabar, because we had toured Senegal and even Gambia. In Gambia there was a group called Super Eagles, made up entirely of Gambian musicians, and they used that instrument, the sabar, in their music.

Does the sabar originate with the Sérères [of Gambia]?

The Wolofs have their own variety of sabar, the Diolas have their own variety of sabar, and the Sérères as well.

The sérères, for example the singer Moussa N’Gom?

He played with us. On the other hand, the way they use this instrument differs from one ethnic group to another. If you know the Touré Kunda group, the way they use the sabar is different from the way we Wolof use it. The rhythms are different.

Can you tell the difference right away?

You can tell the difference right away because it is not played in the same way. It doesn’t have the same rhythm. Even the way of dancing is not the same.

Did having a Gambian [N’Gom] in Super Diamono create a mix within the group?

He sings in Socé [a Manding dialect], it is true, but also in Wolof. In Gambia we speak English, but also Wolof.

Did you also mix different percussion styles in the band?

We did a tour of the interior of Senegal. We went to see the Sérères, who play a rhythm called Ndjoup, to see the Toucouleurs in Fouta (Baaba Maal, you know, plays the Yela), and to see the Diolas in Casamance, who play Djambadon, which is another rhythm. The Wolof, who are the majority in Senegal, play the sabar, but their music is the m’balax. All these different rhythms make up Senegalese music. This is what Léopold Senghor said at the time: «You are in a culturally very rich country. Try to work with what you have». And he hit on a concept: “rootedness and openness”.

So the group was not so rebellious, since they had the government on their side, right?

[Senghor] was a man of culture, because he loved culture; he was a poet. But the content belongs to us. He simply proposed an idea for people to make better use of their cultural resources. But the content is up to each one of us. I, for example, chose a different path by promoting Pan-Africanism. That’s why our music includes songs dedicated to Nelson Mandela. In Soweto [South Africa], I denounced the coups d’état and called for African unity. Why not a United States of Africa? So I sang about poverty, about young people who couldn’t find work, about abused children, about a kind of polygamy that was not properly managed and women suffered because of it, about the importance of educating children, and so on. So I chose topics that were very disturbing at the time.

Was there any risk?

Yes. Not the risk of going to jail, but the risk that our songs would not be played on the radio [laughs], because there was only one station then. [At the beginning] they didn’t play our songs at all. But even so, we already had an audience that was there and loved what we were doing.

You had a weekly residence at the Balafon Club..

It was a club in the heart of Dakar. We have a history with that club, because only fans of Super Diamono’s music went there, people who embraced our somewhat revolutionary ideas. But the others, those who liked the good life, the social life, went to see Youssou N’Dour. [laughs]

[N’Dour had his own regular gigs at a competing club.]

But you were friends with Youssou N’Dour?

Yes.

What did it mean to go see live music in Dakar at the time? Why did people go out and what did that mean for their lives?

People began to understand that there was already a real change of mentality going on, especially among young people, young people from the banlieues [working-class suburbs].

So it was a change of mentality linked to social class?

Of course. Especially among students.

In the 1970s, was there still a certain joy in the air from the recent decolonization & social transformation?

Music was an increasingly important means of communication. Because at that time, being a musician was frowned upon. Being a musician was synonymous with being a thug. We were in nightclubs, with alcohol. So people didn’t understand. Because Senegal is a quite religious country. Even at home, parents didn’t allow their children to play music because it wasn’t seen as something good, there was no future in it. It wasn’t even considered a profession; music couldn’t feed you. It was a street thing, so it was frowned upon. You had to deal with that.

Are you also religious? You belong to the Mouride brotherhood, right?

Yes, that’s right.

You’re close to the community that pilgrimages to the Grand Magal of Touba. There has long been a link between musical genres such as m’balax and Mouridism [branch of Islam], for example as a way of singing praises. Have you ever felt the need to talk about your religion through your music, or is it a social commitment that drove you musically instead?

I have, I have several songs dedicated to the spiritual guides of Mouridism. Because I am Mouride on my mother’s side of the family. My grandmother, who raised me, used to take me to places where Mourid religious songs were sung. When I was 4-5 years old, she used to take me to her marabout every Sunday morning. That’s when I felt something take hold of me, because I loved my grandmother very much. So there I learned some Mourid songs because she often took me there.

When I became interested in the Sheikh, I researched his philosophy and everything he wrote. First of all, he was a bit of a non-material person. He didn’t like material things, no money, no luxury, nothing at all. He didn’t allow himself anything luxurious. I went to see where he slept. He didn’t even lie on the bed, he put his writings there and stuff, but he slept on the floor. He wore a boubou [garment] without pockets and he encouraged people to work, to be honest, to be humble.

These are values that today tend to disappear because we live in a world of opportunists. Everybody is looking for money, for example. To get money, you are willing to do anything, to kill, to do things that are not very lawful, while he was detached from that. That’s why I admired him, that’s why I took him as an example and took the liberty of creating a song about all that, because he is a guide. Despite what is said today about the Mourides, he is not like that.

Today there are millions of people who take advantage. But what he said was clear and unambiguous: honesty, hard work and humility. These are values that tend to disappear today, and everywhere the same, you no longer know who your real friends are, who likes you and who doesn’t like you. Someone once told me: «Listen, we are Muslims, we believe in God, but there are people who don’t. So God has enemies, but they cannot be people, of whom he is not an enemy. It could be an object, a thing.» No one has found it, but I told them that [the enemy] is money.

What you were doing, living the rock n’ roll lifestyle by playing in public.. Weren’t there difficulties in the religious context?

People did not take what we were doing seriously. Senegal is a 95% Muslim country, but there are different religious circles. Here there are the Mourides, led by Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba, there are the Tijaniyyah, there are the Layenes…. They are all Muslim brotherhoods, but they are different, different because of their leaders. So the attention of Senegalese Muslims is dispersed among these brotherhoods. [For the religious authorities] we were a little bit relegated to the role of lost boys.

Can you describe a typical evening at the Balafon club?

You couldn’t come to Balafon Club without liking Super Diamono. It was a pretty special club, because at that time we didn’t praise people like others did [in our music]. We sang about unemployment and Nelson Mandela. At the time, people would come up to me and ask, «Who is Nelson Mandela?” We were a bit marginalized. The people who came to play the Balafon Club were our audience. The other people we called the fashionable people who dressed well, those people went to see Youssou N’dour. [laughs]

Is this still the case?

Yes, it’s always like that. [laughs]

You were talking about serious things, but the atmosphere at the Balafon Club was lively?

Yes, it was lively. We were there too. Because we liked it. Although there wasn’t much money. But we didn’t mind. We enjoyed doing it. There were people there who were interested. We enjoyed doing it. It was really something extraordinary for us. For us, that was the most important thing.

Did you at one point say to yourself, «I’ve arrived, now I’m a music star.»

«I don’t really like the word ‘star’, because as they say, ‘star’ means ‘starry’. I have both feet on the ground, so I’m not too interested in being a star. We had a lot of friends who came to see us. We lived like that and shared everything we had. There was a certain solidarity, we were very happy like that.

No difficulties?

We still have fans. We have created a fan club called AFSUD (Amicale des Fans du Super Diamono). It has grown and become something important. It’s a serious thing. This year I’m celebrating 50 years of music. We are touring throughout 2023. Today, the young people who have inherited the AFSUD fan club, it was their parents before them and it was their older siblings before them, and now it’s a younger generation that has inherited this fan club. So it’s been passed down from generation to generation. That’s how rich this history is.

You’re still the government’s ambassador to Senegalese universities…

Appointed by the President of the Republic.

I understand that Senegal is investing heavily in education.

Of course. The current president, their generation, when they were in college, I used to go there and play parties and concerts for them. And at that time I created a song called Étudiant, which I dedicated to the students. I wrote it in 1988 and it’s still current. I can’t give a concert without people shouting «Étudiant! Étudiant!», in any country. And yet it’s a song that goes back several years. I am someone who means a lot to them. And now there is another generation of students at the university. There are young students who weren’t even born when I created this song who have now adopted it. And if you go to the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar today, the cultural square where they organize concerts and cultural debates, on the social campus, that square is called Omar Pene.

There are a lot of songs about young people and for young people, so why did this particular song resonate so much?

Since no one has done it before, I am the first. And I did it referring to my own background. Without going into too much detail, I grew up on the street. With all the difficulties I’ve encountered along the way. I am well prepared to share all that, because God knows I have had my share of difficulties. In Senegal, people know the story of Omar Pene. So today I have become a kind of role model for them.

The fan club was founded in 1989. At that time there was no internet, but people passed around cassettes?

People passed cassettes around because there was no other distribution channel. We weren’t on the radio, so young people passed cassettes around.

Sometimes you release an album and the next day it’s been pirated all over the place. Was that a positive or negative thing for sales and for your fame?

You could say both. It is a parallel circuit of clandestine distribution. Naturally, because not everybody can afford to buy CDs, for example. They prefer to buy pirated material, which is cheaper but not of good quality. You listen once, you listen twice. And then things go wrong [the quality is lost].

In West Africa at that time, did the album as a concept hold the cultural value it does now? Was the release important? Or was it just songs?

Well, at that time we were always behind what was happening musically. Because in developed countries, for example, people were releasing records, but we, until very recently, still had cassettes. But it was still important to release something because people were waiting for it.

What was Super Diamono’s creative process like?

There were several eras of Super Diamono, and different generations. At the beginning, we went to the interior of Senegal to do some research on our cultural identity, meet the people and come up with something rhythmically speaking. It took us two years. When we came back to Dakar, we were all living together in our own house, all the musicians. Then we started rehearsing, working with what we had brought with us. We had a lot of rhythmic baggage, and we said to ourselves, «Now we’re going to create the Super Diamono style». So we said, «Okay, what are we going to do? Let’s call our music Afro feeling music. It was improvised music. And that was it. And since we were somewhat influenced by Anglo-Saxon music, we tried, through rhythms, to create a music that sounded like us. A music that would take into account what Senghor was saying at the time: rootedness and openness. A music that sounded like our own in the rhythm, with me singing in Wolof, but also open to the outside world, a music that all the peoples of the world could understand, a music of openness. So that Americans who don’t speak Wolof can feel what we do.

Musically, did you start with percussion or singing?

It all started with percussion: sabar, drums, bass. The bass was considered a percussion instrument. The sabar is the metronome. It is the sabar that gives the rhythm.

Like a «clave» in salsa…

The only thing missing are the keyboards to spice it up. As soon as you set the rhythm, you’ve got something. Now everything that comes after that is to give it color.

As a group, did you tend to play with a musical idea for several hours? To let time pass for an idea to take shape?

Everyone contributes something, it’s a collective thing. Everyone brings their own ideas. Personally, I always prefer that people create the music first and then I come and sing. You have to let the musicians agree on the content. It’s a kind of team, it’s a collective. It’s true that I’m the leader, I’m the singer, but everybody has the right to contribute their ideas. It’s open, really, it’s open. What I mean is that everybody has the right to give their best, and that’s very positive for us.

No arguments?

No arguments. When we talk, we talk about music, that’s all. That’s the style: Diamono. «Diamono» means «Generation».

In the first album, Géédy Dayaan (Géeju Ndayaan), the music is very slow, very open. But a few years later, the music is very fast, very tight…

We want to make music that interests people. So we’re not always satisfied with just making something for ourselves. It’s a sensibility and it’s important that everyone can relate to it. Even when we do a concert, we start with that. We start with the slow ones, the cool ones, and then we move up at a very steady pace.

In a concert, a song can go on for a long time?

No, it’s not like that. It’s only four, five minutes at the most. You have to play several songs. We learned that in Europe, because here it’s not the same. When you play internationally in a concert, you have 90 minutes.

In Dakar the concert could last all night, right?

In Senegal, we organize dance parties, which start at midnight and can end at 4 in the morning. [laughs]

Do you have a favorite place to play?

No, no, we go where we are called. This is a band that tours a lot. For example, when I was in Central Park, in New York, there was an extraordinary audience. And what surprised me a little bit was that some people, Americans, were asking us for certain songs. I said to myself, «Where did they learn that? Where did they hear that? I was a little bit surprised. And then I saw people, Americans, dancing to our music better than the Senegalese. It was unbelievable. At the end, we said to ourselves that we had done well to listen to Senghor’s philosophy, rootedness and openness.

When popular music is mixed with traditional music, what happens to the traditional music? Does it get lost in the popular music? Or is it reinforced by the distribution of this music?

The interesting thing today is that traditional music still exists. But what we are doing is modernizing it. Because today’s music, as they say, has no borders. I listen to music from other places. I don’t understand English as such. Maybe I understand the English of tourists. When people ask me questions, I don’t even get it. But still, we manage to understand each other through an interpreter. That’s all. And things evolve, the world evolves, so everything evolves with that global evolution, that’s all. That’s what modernism is.

Is there current music composed by young people that you are passionate about?

Yes. Well, what we can remember from all this is that, as I explained at the beginning, it was not easy for us in our time, because we even hid to do it. Nobody believed in it. Society didn’t accept what we were doing then. But today, attitudes have changed because musicians have succeeded in their lives, especially socially. It has become a buoyant business. There are musicians who are basically successful. All the musicians of my generation, for example, have become important people in our society because they have succeeded. Youssou N’Dour is a company director who employs thousands and thousands of people. Ismaël Lô, Baaba Maal, me, in short, our generation. We still managed to start something, and people have seen that we made a mistake because at the time we didn’t believe in it. But now these people have proven things. But, now, nobody forbids your child to go do music because that’s what it’s all about. It’s fashionable nowadays and, personally, I’m very happy to be part of that generation that worked, that really fought, that believed and that was able to do something concrete. So it’s a good example for us Africans. And that applies to many African countries. If you go to Mali, there is Salif Keïta, if you go to Cameroon, and so on. So it’s the same everywhere.

When you come to France, what does France mean to you?

First of all, the language and the fact that our money is there, it’s simple. It never occurred to me to come and live in France, I prefer to stay at home, in my environment, where I have my customs. Because I cannot live anywhere else but at home, even though I am a man of culture, I am very open, I like to travel and meet other people, just for that reason. I am patriotic, but I love my country and, frankly, immigration has never tempted me. What’s more, I have created a song to ask young people to be very careful because, otherwise, it’s going to be more and more difficult, and considering that rejection is everywhere. I am a convicted Pan-Africanist, I am an Afro-optimist. I have always sung songs about Africa. I have even sung about a “United States of Africa,” why not, because nobody can do things better than us. We can’t wait for others to develop our continent, we have to do it ourselves. We have to think about it. There are men and women capable of making things happen and Africa has all that. It’s a revolutionary idea, I think, because that’s what I am. In any case, I strongly believe in it.

You published an album on climate change. What changes in Senegal’s climate or other problems do you observe today?

It is a phenomenon that affects the whole world. In Senegal we are experiencing it because there is a region in the north of Senegal, in Saint-Louis, where coastal erosion is causing a lot of damage. There is even a village that has disappeared, that has been invaded by water, and it is all due to global warming. In some coastal towns, the waters are swallowing the houses. And the climate has also changed a lot. The seasons have become a bit strange. It’s hardly cold anymore. In December, for example, we used to be cold, sweaters and all, but now it’s warm until who knows when. Since Africa is the continent that pollutes the least, it has been estimated that the pollution level in Africa is 4%. We pollute less, but we suffer all the consequences of the others. And in all this, there are the climate skeptics, in particular the great powers that pollute the most and continue to deny climate change. There are certain presidents whose names I will not mention who say that global warming does not exist. So, at the end of the day, I think we have to raise our voices to talk about this, to raise awareness not only in international opinion, but to say to Africans, «Watch out, stand up. We have to talk, we have to find ways to deal with the situation, because if ever there is a tsunami in any African country, the whole of Africa will suffer the consequences.

We have other priorities, we have to fight poverty, malaria, malnutrition, and so on. We have had Covid, which has killed hundreds of thousands of Africans. So we need something more than suffering the effects of global warming. And all this has inspired me, as a Pan-Africanist, to warn people, to raise my voice to speak to people. Maybe this can lead to some reflection. In any case, I’m working on it right now, and my whole 50th anniversary program revolves around the issue of global warming.

Some governments have proposed climate reparations for the countries most affected by climate change, do you think this is a good idea?

Nothing has been done yet. It’s good that people are realizing that this phenomenon exists, which was not obvious a few years ago. I’ve even heard Joe Biden talk about it, whereas his predecessor didn’t give a damn. This awareness is what is interesting. And I see that even the young people, whom I call “the future,” the young people have stood up today and every time a COP [UN climate conference] is organized somewhere, the young people stand up, they go to the decision-makers with placards to tell them, «Be careful because we are the ones who are going to inherit whatever happens next.» So there’s a collective consciousness that’s spreading around the world, and I think that’s a good thing.

Do some countries have debts to other countries, for example a climate debt or a post-colonial debt?

There is always a debt owed to others because the world was built on things that happened that should not have happened. Those who have benefited from these advantages must recognize that they have taken advantage of the weaknesses of others. They took advantage because they exploited it for their own benefit. So we have to recognize that and then try to make amends, to have the conscience and the honesty to say that we have hurt somebody and now we have to make amends, but how?

Within Africa, are there things that also need to be solved among African populations?

Of course. In April I went to Abuja [Nigeria] to receive an award from ECOWAS. I was chosen artist of the year. There were 15 heads of state there. But what I noticed on the way back was that I traveled from Dakar to Lomé and from Lomé to Abuja. And all along the way there was so much hassle that I thought: maybe we believe in our continent, but there is still work to be done. I realized that it was easier for me to go to New York than to Abuja. You can see the problems we Africans have, and we are talking about the movement of goods and people. You can see the work that still needs to be done. Some people have said to me, «Isn’t it utopian what you are advocating, this Pan-Africanism? But you have to believe in it.

When you were a child, you were not a griot, but now you arrived, you’re a kind of ambassador. Do you feel any pressure?

If nobody is saying that – because there are many precursors – it’s because I did not create it. I found African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Cheikh Anta Diop, Nelson Mandela, Amilcar Cabral, all great African figures, who advocated it. More recently, the young Thomas Sankara, from Burkina Faso, also had a certain pan-African idea. So there are people who believe in it, but the only proof is that it doesn’t suit everyone. Those who exploit Africa’s resources will never want a United States of Africa. Africans must assume their responsibilities.

Are you still playing soccer?

I don’t play anymore, but I love it. It’s my passion. I can spend a whole hour watching soccer. I love soccer.

Which team?

In Senegal, my team is Jaraaf, to whom I have dedicated a song. In France, I support Marseille. In England, I support Manchester City.

In soccer there is a certain intelligence. Well, in sports in general, I also follow the NBA. I love basketball, I was a big fan of Michael Jordan. So there are people like that who have something special, who are unique.

People say that sports is like music, because the showmanship is very immediate.

Yes, athletes like music too, frankly. I’ve even seen some boxers, when they enter the arena, they have headphones on, or they’re followed by a rapper. That gets people moving.

Do you like boxing?

My wife loves boxing, but I, well, I watch it, but I don’t like anything violent.

Senegalese wrestling…

Senegalese wrestling too… I like traditional wrestling. It’s very technical. You don’t throw punches, it’s all about techniques to take your opponent down. But when you hit…

It becomes something else.

Yes, that becomes something else. It’s people fighting like that for money, so we’ll do anything to make money. [Laughs.]

Thank you very much for your time.

The pleasure is mine. I hope to see you again in Senegal, inshallah.

[The interview] was very good. I liked it a lot because we talked about very interesting things: music, career, life. What I liked most about the interview, and I’m glad about it and I congratulate you, was that we didn’t talk about politics. And thank you very much for that.

Pingback: Omar Pene: «A través de los ritmos intentamos crear una música que sonara a nosotros, que tuviera en cuenta el arraigo y la apertura» - Jot Down Cultural Magazine

Pingback: Omar Pene: “On a essayé de par les rythmes de créer une musique qui nous ressemblait, qui tenait compte de l'enracinement et de l'ouverture” - Jot Down Cultural Magazine

Pingback: Omar Pene: «A través de los ritmos intentamos crear una música … – Jot Down – Lavozhispana: Información que trasciende los titulares

Pingback: Omar Pene: “Dañoo jéema boole ay tëgin ngir am sunu yëfu bopp, fent ab misik bu mengoo ag lu Senghoor daan wax sampu ak ubbeeku” - Jot Down Cultural Magazine