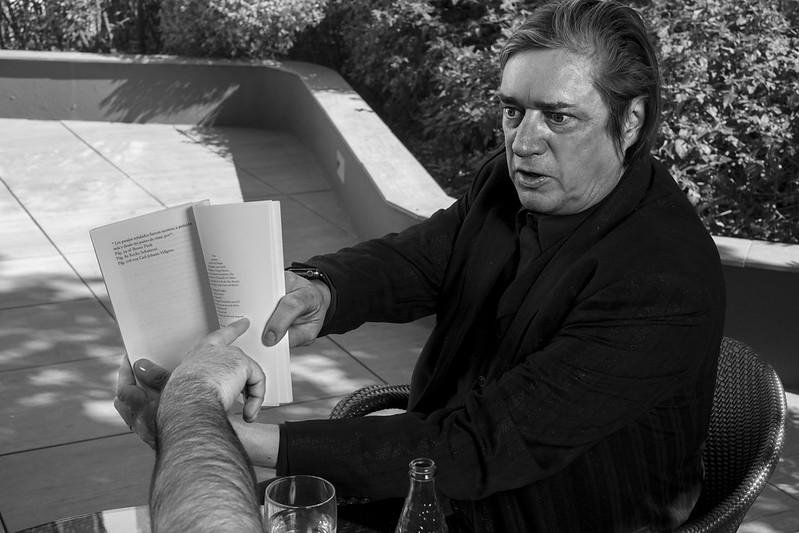

Photography: Óscar Fernández Orengo

(Versión en castellano aquí)

As you will see in the turbulent start of the interview, Blixa Bargeld (Berlín Occidental, 1959) has come to the Kosmopolis CCCB festival in Barcelona to talk about his book and offer one of his solo vocal performances, and he doesn’t seem very inclined at the beginning to talk about his long and fruitful trajectory: singer of Einstürzende Neubauten, guitarist for Nick Cave’s Bad Seeds until 2003, music and vocalist with Alva Noto or Teho Teardo, actor, theatre director, performer, composer… Certain discrepancies with the Spanish edition of his litany put him in a bad mood, but after seeming for an instant like if he was going to rip my head off and use it as a handmade drum, he relaxes and answers all questions very politely. He speaks with precision and clearness, and we end up talking about, amongst other things, the tension in silence, anarchist self organization, preeminence of context over sound, the birth of crowdfunding or the future of art.

We have not much time and there are so many things I would like to ask you about your trajectory: your solo performances, Neubauten, your writings… I’m a great fan of your work. I’d like to start talking about your usage of the voice.

So this interview is not about the book.

Well, not only that…

That’s interesting. I’m here to promote the book. I was not prepared to do any interview about Neubauten. It’s a bit unfortunate. I have to reassess if this is at all possible. Hartmut! [Calls his assistant] I’m here for a literature festival promoting the book! Why am I sitting here answering questions about my artwork, trajectory or Einstürzende Neubauten? Have we done a concert here, have we just released a record?

I’d love that, but the interview will be about your whole trajectory, not only Neubauten.

OK! Good! Sorry about that. Ask your questions!

I was saying that I would like to talk about your usage of the voice. You have defined yourself sometimes not as a musician but as a vocalist, in the sense that you use the voice as your main weapon…

No, I don’t like weapons.

Yeah, you’re right, I read that you didn’t like to be called a vanguardist because it sounds too military.

Exactly.

Let me rephrase… Voice is your main instrument. How did you train yourself to use, modulate, place and change that voice, from whispers to your recognizable scream?

Learning by doing. I have no formal training as a singer, but at some point in my career as a singer I realized I could do some things with my voice that are fairly unusual, and I strengthened those aspects. I trained them, so to speak. And what was at first maybe erratic or with mistakes, it became just more and more of my palate of things to do with my voice.

I’ve seen in a beautiful video how you do a solo vocal performance with your daughter Anna Bargeld running in the background and looking very relaxed regardless of your screams…

That was in Vienna. [Smiles] Sometimes you can’t stop her getting on stage. Once she started singing the Chinese version of Frère Jacques. In all the different versions of that song it’s usually about monks and the morning bells, but the Chinese version is about two tigers. So she sang the two tiger version of Frère Jacques. [Laughs] She also performed once a dada ballet on music by Erik Satie, when I had to do a solo performance at a dada festival. That’s maybe online too, somewhere.

About the lyrics you use… During your first years you said you were mostly improvising on stage. How did you plan those improvisations?

It was a different story for each song. Improvising lyrics leaves you, most of the time, in the rudimentary forms. Later I started improvising around certain ideas. A bit like making the skeleton, throwing things at it and sometimes they stick. Later I started making notes and writing things down in scrapbooks… Around 1993 I bought my first computer, and I made it a routine to write daily. I still write by hand most of the time, but then I type it and do a bit of work on it. I have a huge corpus of notes and ideas, and that’s what I throw around in different ways. When I work with Neubauten it’s most of the time very closely connected to the music. It is usually the process of musical ideas first, and then I react to them, and then that reaction forms again the material. It is different if I work with Teho Teardo; and when I was working with Carsten Nicolai, on ANBB, I devised a whole complete way of language that was more suitable to the abstraction and the minimalism that is coherent with Carsten’s work. The whole Mimikry album, it’s language-wise far into abstraction.

Mimikry starts with a scream prolonged for some minutes, a nice way to start…

That leaks over from my solo performance… It is collaboration, but I performed a version of that even before I made the album with Carsten.

Which influences did you receive in your way of writing? I’ve read in Jennifer Shryane’s book that the writer Heiner Müller was an influence, for instance.

I visited him a couple of times… He used some of our music, and I directed a radioplay based on The Hamletmachine, so there was a bit of collaboration going on. I really liked things like Bildbeschreibung and The Hamletmachine, the way he used what he called head theatre: at the time he wrote The Hamletmachine he never thought that this ever was gonna be put on stage. I think I probably have included some of that theatre textual structure into some of the things that I’ve done with Neubauten. Sie on Tabula Rasa is written like it could be a head theater play.

I read once a quote from you about Neubauten: “I could say tomorrow that we are no longer a band, but a theatre group and still be doing the same stuff”.

In the music industry, as a band, you’re making a successful record, and then you do the second record where you change the formula but not really very much, and you’re gonna continue making the same thing over and over again. If you are a theatre group you could prepare a completely different play every season and nobody would ever say “this is not what you did last season”!

You said once: “music has to offer the unthinkable, something beyond language”. How do you try to go beyond language?

I wouldn’t know how to answer that question [both laugh].

OK, so let’s go back to language… Neubauten has been credited sometimes as one of the forces behind a certain rehabilitation of German language into the Arts.

Many other people have done that too, but it is certainly true that in the ‘80s, when we started, the legend was still that you can’t sing rock music in German. People kept telling you that. Nowadays it’s so full of bad German lyrics and bad German singing that it’s really disgusting.

Here I have the Spanish version of Europa Kreuzweise, it is a litany, so it sounds well when…

[Interrupting] You just said the German title, have you noticed something strange in the Spanish title? It’s only Europa. I don’t understand why did they change the title. Neither Residenz Verlag, the Austrian publisher that originally published this book,nor the Spanish publisher contacted us. So, nobody ever asked us if we are OK with this translation… Or why is there a Neubauten logo in the book, which is a registered trademark. And they just put some comments in the end here, that I don’t know anything about. And then they print lyrics… Those are gross mistakes. But the main thing I really don’t like is… Where is the Kreuzweise? You can say “back and forth”, “alto-bajo”, however you want to translate it, it doesn’t need to be a cross. But it’s not a book about Europe.

Let’s talk about Europa Kreuzweise, then. I’ve read the Spanish version and liked it a lot, I don’t know about the translation…

I believe it’s OK.

Did you write it like a travel journal and then polished it and put it together?

No, it’s fiction. It’s put together: partly is true, partly is not, but the sequence as it is written in the book never happened. So of course if you put a Neubauten logo on it it looks like I’m writing a tour journal, but that’s simply not true. I have been to El Bulli, but not on this tour! [Laughs] Many things actually were not happening at the places where I describe them, others actually did. I wanted to follow the format of a litany, in its original classic religious context of a verbally uttered endless repetition of the same formula. That’s why there is a setlist repeated in there… If you read it aloud you see that the rhythm goes on and on. I didn’t try to document neither Europe nor the Neubauten tour, I just wanted to construct this kind of an oral format of a litany, because that was what the publisher asked me to. They had a whole series of litanies written by different people, all of similar length. I worked with my old compaignion Dr. Maria Zinfert, and I asked for her literature opinion about what a litany is; I worked close around those lines and wrote an oral text that can read loud. How much of that in there is true and how much is fiction is not really important. It’s not about the Neubauten tour and it’s not about Europe. In a way, of course, it touches all that and it has a lot to do with it, but it’s not my original intention.

The book mentions a lot of cities which could be considered a single city. Prague, Helsinki, Moscow, Bern… You look like a pinball lost in cities that are all different and all the same. Do you feel like Europe is a single city with different neighbourhoods?

It’s rather sad… First of all, yes, I travel from city to city. It is not happening that often that we are in rural areas to make concerts. And it’s shocking how similar the city centers are: all the pedestrian areas of cities in Europe have the same shops, in Madrid or Helsinki. I use little Moleskine notebooks, but I know that if I go to Helsinki I will be able to find one. I don’t need to go to this one place in Paris in the backstreets where they originally made them. I can have the Moleskine bought in the airport, and I’m sure that here in Barcelona there’s a Moleskine shop too. But as I say in the book too, if I want to buy shoes I do it in Italy.

Talking about cities: you created with Neubauten the soundtrack for Siegert’s documentary on the reunified Berlin: Berlin Babylon. It closes with Die Befindlichkeit des Landes (The Lay of the Land), quite a melancholic song. How has your perception of Berlin changed from the eighties to now?

I left Berlin in 2002, first to San Francisco, where we had a house for twelve years or so. And even keeping the house in San Francisco we went to Beijing… When we finally went back to Berlin, because of work reasons for my wife Erin, not for myself, we ended up in Mitte, which is formally East Berlin. That was for me terra incognita, I had no memories connected with that city. I was in fact in Berlin, but not in the same city. When I go through the Tiergarten tunnel and I come out in West Berlin, I can say this is where my dentist used to live, that is where my first girlfriend was… But if I go back to East Berlin there is nothing, it’s basically white. That’s good in some sense. Everybody knows that Belin has changed… Of course it has changed. I am de facto in Berlin and in the same time I am not in Berlin, or in the West Berlin I grew up. I am in a different city.

You directed recently a documentary for ARTE’s program “Square Artist”, dedicated to the political activist and musician Dror Feiler.

Ah, you’ve seen that! Good! I’m happy to hear that some people have seen it. He’s an incredible character. He has written a composition for me as a vocalist, with orchestra, and performed that in Norway and later in Athens. Good Dror, yeah. What do you want to know?

Why did you choose him and how was the experience?

It came naturally, somehow. The format for Square Artist is called carte blanche, freedom to do fiction, or a documentary… That was the start of a compositional process with Dror. He was in Berlin, we recorded something, we started filming. Of course, he’s not only a composer, a performer and a musician, he is very much a political person, running for a district mayor in Stockholm… And he is also the head of the European Jews for a Just Peace, and the one that did the Ship to Gaza. Big deal. [Takes his shoes off]

One question about your performances… Why do you choose to appear barefoot in many of them?

Not today… But… I can pick up things easier from the stage floor. It’s not just me, Alex on the stage is also barefoot. If he has no shoes on, I can feel it and he can feel it. [Taps on the floor with one feet] If I had shoes, you would hear click, click, click… It’s a very easy aspect. We’re locked in together with each other, we follow the same metrum because I can feel the tapping of his foot with my foot. You should try it, it’s a very useful thing.

Why not… [taking my shoes off].

I tend to say that stage time is not normal time. I cannot go on stage wearing the same clothes, so to speak. I have to make a clear change when I go from my normal space-time continuum to stage time. Stage time is a holy time. Somewhere I wrote that when I’m alone on stage I pray. Today I will be alone on stage. I have no preparation, there are no samples, no backing tapes, nothing that can hold me somehow… So I have to open up a channel and let it flow. If I’m not able to do that then the performance falls flat. It hasn’t happened yet, but it can still happen today, you never know…

I’m sure it will be right. We talked before about your usage of the scream, but you also use its contrary, silence… In Silence in Sexy, one of my favourite Neubauten songs, many saw an homage to John Cage.

Sure! Mute Records has just released a jubilee album for their 40 years, where all different Mute artists perform a version of John Cage’s 4’33’’. And we already had it on tape: we just had to use the silence from Silence is Sexy and cut it into four minutes and 33 seconds in length. [Laughs] The formula for Silence is Sexy was a one take recording: we recorded as often as we needed to do until we got it. There are two different endings, the one in the album where you hear the audience in Mexico City singing Silence is Sexy, and the original ending where you just hear us in the studio, when the last note is dead and we go softly “yaaaaah”, because we knew that was the take. But before we recorded that, we had a whole reel-to-reel tape of the band with instruments, amps, and all the microphones turned on, but not playing anything. Just staying there, because I wanted to know how much of the tension would actually transport into the tape. There was a different intention in what we were doing there to John Cage’s 4’33’’. In his writing he said that you can hear the noises from outside, and it’s all part of the composition… But I was interested in how much tension could there possibly be in silence, and how much of absence. That was my starting point when working with Silence is Sexy: absence and tension. Not the zen-like meditational silence, but tensioned silence.

It must be a difficult song to perform in gigs, I guess…

No, there’s an aspect that I like, and it becomes obvious when we play it. There are really long silences in there, and some idiot in the audience will always try to use it to scream… But then others will silence that person. So that moment frees the force of self-organizing entities, which is an anarchist ideal, in a way. I like that. We’re not doing anything: somebody is disturbing, and then others will form somehow to avoid it. And it works, nobody has ever really fucked it up.

You mention anarchist organization, and that takes me to the Neubauten Supporter Initiative that Erin and you started to avoid depending on record labels… There was some kind of self-organization going on within.

There was a bit of self-organization there, yes. In the last period, Phase 3, we told them that there would be a big supporter event. And when we were offered to play in the not yet demolished Palast der Republik in East Berlin, we decided that would be it. It’s not to be mixed up with the released video, that’s from one day later, but before that. We played with no barricades, no stage, no security… People were getting up at five in the morning to help transport the packaging to the hall, Jennifer Shryane later wrote the book, other people did other preparations… They organized all themselves. It was beautiful, one of the highlights of our life career, in a way, to be able to play a concert with no financial side to it and no security. That gives you a little bit of hope about that some self-governing structures are thinkable and doable. And that of course does have some political aspects.

In Was is ist the choir seems also to be organized.

That was the so-called Social Choir: a hundred supporters went to choir rehearsals, we developed a different language with signs for all things to do…

You were somehow acting like a theatre director.

In a way, it is very often that I’m acting as a director, yeah. I direct musical material.

You used for the participants the word Unterstützer (supporter) instead of Anhänger (fan). Active supporters more than passive consumers or fans.

It is also a structural term. There are beams in a building that give structural support, and the building is in this case Einstürzende Neubauten… They act like a beam that supports the structure. That was my train of thought. But, of course, in England you also call the follower of a soccer team a supporter. [Laughs]

Alles Wieder Offen record was financed entirely with supporters, so there was no commercial record label behind.

It was fully funded by supporters, yes. We started Phase 1 in 2002, that’s when Erin invented crowdfunding. Funny enough, now the Stanford University wants to buy our whole archive, because it’s the beginning of crowdfunding.

Showing your creative process was one of the part of it, not just the rehearsals but the whole process; that’s risky, because some people only like finished products… But it helped to build community.

I don’t know if my intention was to build community, but I guess that for a normal band it wouldn’t be that interesting to show that process. We will do the same thing again this year: we’re doing Phase 4 now.

Around that time you started to burn CDs of each concert, package and sell them “on the door” just after the show…

[Laughs] Clear Channel tried to stop us. We had to give them a symbolic dollar, for them to grant us the right to continue this, because we could prove to them that we have been doing that a couple of years longer than they are doing it. At least in Germany it doesn’t matter… I haven’t been in an American tour for a long time, I guess it’s even more restrictive and if we tried to sell the CDs the venues wouldn’t allow it. Now we’re just doing it with USB sticks, but in the original run we also included a photo of the show in the cover: we had a small photo printer, so we would take a photo from the first song and then print it on a self-sticking photo paper inside the double white cover for the two CDs, so you would get the magical thing of an actual double-CD record of the concert that you have just seen with a photo of the concert itself [laughs]. It is possible!

Also for supporters you did some experimental recordings, the Musterhaus.

For a couple of things that were outside album material. But sometimes it did feedback with the work in process… The work with glass on the last one found its way back into the actual work in the album too.

This last one is almost silence, because it has you all sipping wine…

It has glass sounds… You can see it, it’s like a little play. There is a play on the CD that it’s a bit like Beckett, if you ask me. Beckett made these strange films with four dancers here and four there, in different colors, and they go from here to there, and then the structures get more complicated… But nothing happens. And in the CD there’s a wordless wine tasting as a similar play: nothing ever happens, but there’s a ritual about picking the glass, tasting… It’s a hilarious piece of work. We had the money from the supporters: we wanted to do a theater play, so we worked for two days, we built the set and just did it, streamed and released it… Without nobody telling us that we couldn’t do it. It was great work, I liked it.

There was another Musterhaus about cassette recordings, right?

Yeah, that one was a bit limited because Johann and Rudi had nothing to do with cassettes, so it’s basically Alex and me.

You tended to use very much cassette recorders during your first years. I’ve read about a cassette recording done in an Autobahn bridge with Unruh…

Inside an Autobahn bridge, actually.

What were you trying to create in that recording?

The soundscape inside that bridge was enormous. It was 1981. I knew this place since Elementary School, and I was just looking for a place that was part of my culture but also in between normal places. Something urban, with debris… Sometimes we just made expeditions, taking recording equipment and going from a supermarket to a subway station, a bar in Kreuzberg, a water tower or the old tramway system, and make recordings with whatever we found there. There was another piece included in the Musterhaus, one I recorded back then in 1979, where you just hear different atmospheres from morning to night. And when you hear now what the sound on the street was, even in the soundscape you can tell this is not 2019, but something like from fifty years ago. There’s a different sound even to the traffic noise.

In those years you used a mixture of self-made instruments, found objects, drills, hammers… Sometimes from construction sites: there was a saying about that, I think.

That was Unruh’s saying, it’s from a building industry advertisement: ”Sei schlau lern beim Bau” (be clever, learn at the building site), so he just modified into “Sei schlau, klau beim Bau” (be clever, steal from construction site). That was written on his first self-made drum set.

Handmade instruments have accompanied Neubauten for a long time, even for the Alles Wieder Offen record.

I’m not so much the instrument constructor. I am a constructor of concepts, I don’t do much manual construction.

Not manual, but the task of putting together all the sounds..

I’m also not that much interested in sound. Sound is highly overvalued, context is interesting. Sound is not interesting. Everybody always talks about sound, like if sound would really mean anything. They spend an afternoon in the studio trying to find the best drum sound, without realizing that the best drum sound is the one that makes more sense within a particular context. There is no sound better than another. It’s interesting to find techniques and strategies to overwhelm an object, give out and utter its soul, somehow, but I’m not interested in the sound. If you tell me: today we’re making a record out of bread, then I’ll work with bread, I’ll develop a strategy to get something out of bread, but I will not judge saying “this is a better bread sound or a worse one”… I have to find the context that makes this play with bread a meaningful thing. [Dogs start barking on the background] They know what I’m talking about!

What do you think is the future of art? Art has been pronounced dead many times…

The Green Party is just starting a campaign for the freedom of art, and they asked me to make a comment on that. I turned it around and said that not the freedom of art, but actually the art of freedom is what defines art; you have to take freedom. Freedom is not something that is just there or will be granted, freedom always have to be taken. I haven’t got yet the final conclusion to what I’m thinking there, and I haven’t said it yet in a statement for the Green Party, but I think that it will be something along those lines. Art is not dead, because freedom is not dead.

Pingback: Pašuzlabojuma grāmatas | Digitālā Klade