Report made with the support of Oxfam Intermón

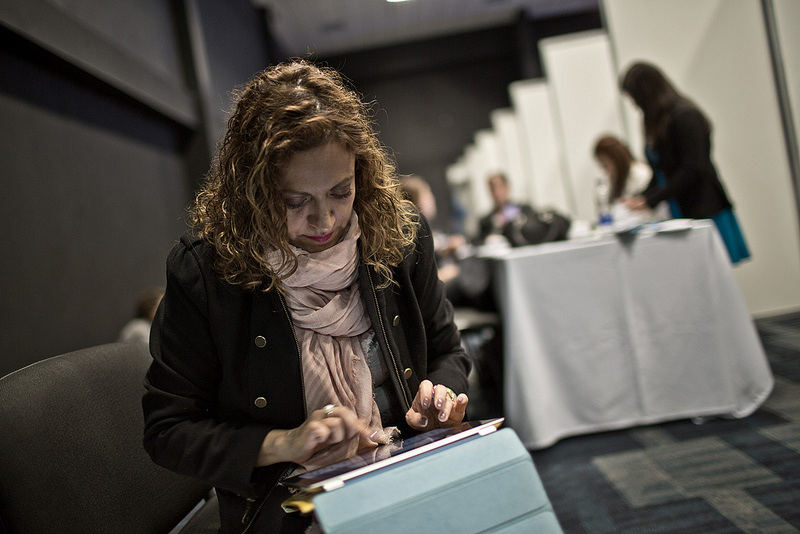

The paramilitary forces invaded the village of Condoto, tortured, raped, murdered and established their laws. For example: women were forced to wash their clothes, prepare their food, stay at home after sunset, they couldn’t wear short skirts nor short hair. María Eugenia Urrutia, an 18 years-old black girl, couldn’t take it anymore, so she shaved head, put on a thong, crossed the village running, went almost naked into river and started swimming up and down.

While the paramilitary were shooting at her, seizing the harvests and expelling the families from their craft mines of gold and platinum, María Eugenia insisted on defending by swimming to her small territory: the beach of the river Condoto. It wasn’t like any other beach.

She was born in the city of Cali in 1966. Both of her parents died when she was 10. Left without choice, she went with her three brothers to Condoto (Choco region) —their home town in the equatorial forest. Chocó inhabitants are 12% indigenous and 82% black, descendants of slaves from the Spanish Empire sent to this region to extract gold from the rivers. María Eugenia Urrutia has the old mark of slavery (a Basque surname) and the old mark of rebellion (a black skin which she exhibited when she was 18, wich was badly injured) and now she shows it again with a mix of risk and pride.

The day she arrived in Condoto, a 10-year old orphan, she left her uncle’s house and crossed the village slowly. A newcomer from Cali, she was surprised by the small houses without electricity with the doors always open. She liked the small orchards, the hens running around, the banana plantations, the corn fields. When she saw the river she got very excited. Her body was full of excitement. The men were fishing in crystal clear waters, the women were washing clothes and the children were swimming naked between the river and the forest. It is a paradise —she thought—, a gift from God after the death of my parents.

When she turned 15, she was sleeping on the beach, quite often. Her aunts were afraid that the waters could rise and take her away. That was the fear. In Condoto no one thought that a girl sleeping alone on the beach could be bothered.

The beach of María Eugenia had a danger: it was one of the most remote and envied within the country’s territories. In the first quarter of the 20th century, Colombia became the world’s largest exporter of platinum, and half of all its production came precisely from the Condoto River. It was a time of extraordinary profits. And as the Economist Claudia Leal explains, everything was exported out of the country: the Choco Pacific —part of a United States mining consortium, was sending shipments of platinum to New York without paying a single penny to the Colombian State. This outrageous looting lasted ten years. Then, for five decades, the company paid ridiculously low taxes thanks to a permanent game of corruption and accounting pitfalls. Despite the delicious deposits of platinum, gold mines of high-purity, untouched woods, fishing and animal stock, Chocó remains the poorest region of the country: in 2012, 68% of its inhabitants lived in poverty, compared with the national average of 32%. The main reason is that it is a region neglected by the State, with very little presence of the institutions, without investments or infrastructure, abandoned in the hands of oligarchs who appropriated the resources by force, blood and fire.

This is where the paramilitary came in handy working as an outpost, invading villages, terrorizing inhabitants and throwing them out of their homes. Once cleared the territory, large mining operations took place, endless cultivations and drug trafficking routes. Those paramilitary were born as right-wing bands, often organized by soldiers and police officers, to fight against the communist guerrillas such as the Farc and spread across Colombia in defense of the interests of certain landowners and drug traffickers well connected with politicians and senior officials of the State.In Chocó, the paramilitary unleashed a brutal campaign in the mid-1990s to throw out the “black” communities, control mining, extend coca farming for drug trafficking and African Palm Tree for agro-industry.

The campaign was a response to the “Law 70” of 1993, which recognized Afro-Colombian communities’ collective ownership of their lands. For the first time they had the ability to negotiate or reject the holdings. The paramilitary then went through the people of the region, house by house, with lists of names of the owners of mines, fields and means of transport. Killing them was not enough: they tortured and raped in the most horrible ways, just to terrorize residents and get rid of them.

Colombia is the country with the largest number of displaced people using force: 5.087.092, more than 10% of the population, according to the Unit for the Victims. They drive them away from their territories, which then pass on to the hands of a few: Colombia is the eleventh country with biggest concentration of land, according to the Gini index of inequality. Rural poverty grows; the income distribution is the most imbalanced of all America and multinationals go around the laws to extend their possessions: in September 2013, Oxfam Intermón reported that Cargill, the largest company for agricultural raw materials in the world, had created 36 smaller companies to acquire an area thirty times higher than allowed by law to a single owner. State lands, destined by law to help the indigenous households.

The women of Condoto were always half naked, said María Eugenia with the breasts uncovered, and no one was curious, no malice and no danger. It is a very torrid land, people go out scantily and that is normal. Therefore when the first paramilitary wave came in the 1980s and they dictated their standards of clothing, she, an adolescent, put her bathroom dress in her bum to make it seem like a thong and swim almost naked, as a ceremony of pleasure and resistance. Then they started to rape the women.

They were breaking the doors and going directly for the mothers and daughters. If someone in the family started shouting, they just blew their head off. It was an outrage. The fear and the shame did not let the raped women talk. They just did not understand what was happening —remember María Eugenia. They felt guilty for not wearing longer clothes. I organized meetings to tell them not to feel ashamed, and to help me report about all of that. Awkwardly that made me a Leader.

The paramilitary wrote down María Eugenia Urrutia’s name. They slipped her threats under the door, insulted her on the street, and cornered her to scare and send her a message. Whenever she sent letters of reports to the institutions in Bogota, the paramilitary returned the intercepted ones.

—One day in 1998 three armed men came to my house. They tied my husband. Two of them beat me, tortured and raped me in front of my three young children. They did everything they wanted with me, in front of my whole family. I was pregnant. The paramilitary offered my husband to join them. He did not resist. The only thing he said before leaving was: ‘I would rather be dead than live with this humiliation’. He cared about his manhood more than his wife and children. He left and I never saw him again. That same night I ran away with my children. We climbed on an old canoe and went upstream, paddling with our bare hands or just using branches hanging over the river. We found a small house on the shore, lit by a small oil lamp, and the man who lived there gave us a place to spend the night. On the next day, paddling again, we found the Red Cross. Someone had to tell them, someone had to show the truth. They helped us to get out of the river and sent us to Bogota. When we arrived I lost the baby.

—Our family had gold mines and a farm with fields full of fruit trees —explains Luz Marina Becerra, another black woman thrown out from the Chocó.— The paramilitary accused us of collaborating with the guerrillas. It was just an excuse to chase us out. They accused the peasants of giving food to the guerrillas and seized all of their harvests. Those who owned boats were accused of transporting the guerrillas and were exterminated almost immediately. They gathered everybody on the village square, picked a man, beheaded him and started to play football with his head while laughing and firing their weapons in the air. They tried to recruit my nephews, but when they refused the paramilitary shot one of them and tied the other one to a tree while spilling gasoline all over him and just set him on fire. One day they came home, beat my mom, tortured me with a long rusty nail, slit my whole left leg and left me some very deep wounds that later became infected. In the hospital I almost got it amputated. Thankfully it improved at the last moment, but I was left with large scars and now I am ashamed to show my leg or put on a swimsuit. Another day, in 1998, we returned from the harvest to find our house totally shattered. They were coming back for us. We picked up some clothes and escaped, my husband, my three year old son, my mother and I. We ran away using the river and then overland to Bogotá.

Luz Marina Becerra and María Eugenia Urrutia, the two expelled from Chocó, have arranged a meeting in the centre of Bogotá but both arrive late from their suburbs.

—They didn’t give us gasoline— Luz and María explained.

Both of them now live in the nation’s capital. Becerra is 36 years old and is President of “Afrodes” (National Association of displaced Afro-Colombians). Urrutia is 47 years old and owner of “Afromupaz” (Association of Afrocolombian women for peace). They give support to the raped and displaced victims, presenting charges against the aggressors and in response they have received threats, beatings, shootings and violations.They asked for protection back in 2010 and the state declared them «at special risk». Even so, it took almost a year to receive the protection they need. Now both of them move around with a bodyguard and an armored car, but the state does not always give them money for gasoline and without a dime in their pockets they sometimes need to stay home or travel on their own risk. This time they have managed to come by taxi with their personal bodyguards.

—A simple explanation of our life: we walked through a forest and suddenly we found ourselves in front of a tiger. We ran among the trees and again encountered another one. Got back to running and again back to find us with another —Becerra, says with an apathetic smile.— We left our land running away from those tigers almost always with our small children and no one wanted to help us. They just closed the doors in our faces. They believe that Afro-Columbian women are only worth for cleaning houses or prostitution. Nobody gives us employment, nobody would rent us a house and our children always get slapped at school. We are women, black, poor, rural and displaced by a conflict: they must have done something bad —people say— or maybe they are with the guerrilla. We suffer all kinds of discrimination. If we organize and demand our rights, people just attack us physically or psychologically.

At a United Nations meeting, Luz Marina Becerra presented a report about the persecutions and discriminations suffered by displaced Afro-Colombians, with strong complaints against the State and she did at an official UN gathering in front of important leaders, politicians and soldiers. Then more tigers began to haunt her. The first one was a man in an overcoat and dark glasses, visiting the office asking for personal information, offering positions in public institutions and proposing her an interview at an already suspicious mall. Luz refused to go. Later it was discovered that the paramilitary abducted and murdered their victims there. A few weeks later, other three tigers with sunglasses pursued the official secretary of “Afrodes” as she left the office and seized her. «No, this is not Luz Marina», said one of the Tigers, and then released her.

The Black Eagles paramilitary group published a pamphlet in which they threatened Luz’s life. At the same time another Afro-Colombian leader, Ana Fabricia Córdoba, was killed in a bus in Medellin. Becerra, afraid, left exiled to United States, where she spent two seasons, but could not bear and returned to Colombia in July 2012.

—I could not stay there. I had to keep fighting for my country.

María Eugenia Urrutia also ran from one tiger to another. When she arrived in Bogotá fleeing from the paramilitary, she encountered hundreds of women exiled, lost in the big city with their children and organized groups to claim their rights and to denounce the aggressors. I became leader «accidentally», she always says. One day, leaving the office of “Afromupaz”, several armed men kidnapped her and her friend. They were taken to an abandoned house, tortured and raped during a whole day. Afterwards the tigers showed them all of the allegations and the reports the women had been sending to the prosecution. The tigers had a source inside the district attorney´s office. Urrutia did not surrender and found other ways: she showed her face in an interview for the national newspaper “El Espectador”. The Tigers attacked with even more fury. Other four members of “Afromupaz” were raped, someone threw a smoke bomb inside María’s house, she was abduced in a taxi, but she managed to escape after a mistake made by one of the kidnappers. Then she had to close her small restaurant when two men arrived on a motorcycle and entered shooting their firearms and screaming: «Black bitch». At that time Urrutia already had a bodyguard, who dragged her into the bathroom and returned fire at the attackers.

—We are not victims: we are survivors —said Urrutia. Because we just don’t give up. We are fighting for our rights, we denounce the negligence of the state and its complicity with the aggressors, and we question the power. That’s why they attack us. Despite all the violence, we have never used a weapon. All of the powerful men, the legal and the illegal, now sit at a table negotiating in Havana and say they are going to make peace. Look, maybe they can stop this conflict, but the peace is made by us, by the women giving their lives from the beginning. Everybody is attacking us —the paramilitary, the guerrillas, even the public forces. And our goal is to build a society of justice and peace, because we don’t want power, we want our children to live in peace, to live freely and go to the beach without any worries.

The sexual violence against women is used by every side. The Constitutional Court of Colombia in Auto 092 of 2008 sentenced it like this: «It is a usual practice in the Colombian conflict, extended, systematic and invisible, applied by all armed groups, illegal or in some cases by the same public forces who swore to protect them»

Sexual violence against women is a war strategy. That’s how is defined by the report — ‘Colombia: memories of war and dignity’, from the national center of historical memory, of 2012. The fighters use it to destroy women leaders who lead political movements, indigenous communities, associations of victims, human rights organizations, to anyone who show his face against the paramilitary, guerrillas or even the public forces. They also torture, rape, and harass the wives, girlfriends, daughters and other relatives of the enemies, because they understand that it is another way to punish and humiliate them. Often they use violence against women to destroy their freedom: those who refuse to take care of the house, to dress according to strict codes, to act with discretion, are identified as «witches», «gossipy», «unfaithful», and they are punished with violations, haircuts, public humiliation, forced labour and slavery, sexual and domestic. Violations are also used as ritual of connection among the men of an armed group, as a reward or booty.

Sexual violence against women still remains unpunished. Between 2001 and 2009, 489.687 Colombian women suffered those attacks because of the armed conflict, according to a study made by “Oxfam Intermón” and the “Casa de la Mujer”. Daily violence is much more abundant, but the study only shows cases related to the war: rape, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, forced sterilization, sexual harassment, forced domestic services and regulation of social life. Those who raise voice always get to a dead end. The Constitutional Court selected 183 cases of sexual violence, the most serious and obvious, and ordered the prosecution to investigate them on a priority basis. Five years later, the result was three sentences.

—We defend ourselves with sticks —says Ana Secue, 42 years old indigenous. The Cauca inhabitants were left with nothing, without homes and without fertile fields. Now they have to live up in the mountains, in autonomous reserves, caught in the fighting between the Farc-EP guerrillas and the army (Revolutionary Forces of Colombia – The People’s Army). The region is covered with crops of coca and marijuana, cut by the routes of drug trafficking and witness of the most violent battles of the Colombian conflict.

In 2002 the nasa, the misak, the yanaconas, the totoros and the kokonucos organized an amazing Indigenous Guard: peace corps, made by men, women, children and elderly, attacking the territory of the fighters to get rid of them once and for all. Their only weapon is a traditional wooden cane.

—With this stick we challenged those armed aggressors —says Secue, while walking through the streets of Santander de Quilichao, a city outside the reserve without any kind of laws.— If you want to shoot me, do it. If you want to kill me, kill me, but am not going to leave my territory, my home. And if you think you are brave, grab another cane and fight with me as an equal. The cane isn’t really a weapon: it is a symbol of moral authority. We believe in ourselves and our cause.

Ana Secue was three times Governor of the Caloto district, one of nineteen indigenous reserves in Cxhab Wala Kiwe, «the territory of the great people», in northern Cauca. She crossed the mountains carrying only a red and green scarf (colors of indigenous peoples), and a cane on her back. The cane made of palm shoots, decorated with colorful ribbons, was the symbol of her mandate. With only a cane, heart full of rage and the power of the unarmed crowds, in those years the Indigenous Guard has captured guerrillas, released kidnapped people, fought troops of the army, confiscated and burned trucks loaded with coca and marijuana that crossed their lands.

—They kill us everywhere —says Secue—. The guerrilla attacks our people again and again, the army installs its bases in our territory, fires mortars at our homes, bombs schools and hospitals. Controls are mounted on almost every road. There are shootings, kidnappings and killings of indigenous leaders without any kind of justice. We do not want anyone on our lands, guerrillas or paramilitary or soldiers or anything.

When the toughest clashes take place, with machine guns, artillery and helicopters, the Indigenous Guard organizes the transfer of all the inhabitants, wrapped in white sheets, to specially prepared shelters with enough supplies for several days. But many times the battles between guerrillas and soldiers took place in the middle of the people’s village leaving them with no chance of escape.

—I’ve seen many men, women and children falling down —says Secue— and out of rage and sheer impotence, I just forget about myself. In a shootout in our village not so long time ago, soldiers killed a girl and left several children wounded. I was in a room watching a young girl dying and I went out, with the cane raised upon my head, to face the soldiers… I managed to scare them away. When I came back to my house, I began to tremble: what the hell have I done, me, a mother of five children, getting in the middle of a shootout… I just forgot about myself.

Secue also took part in the demostrations of women surrounding the camps of the guerrillas and the soldiers.

—With the Farc it is more difficult because they move a lot. People warn us, but on the very next day the Farc move their camp to another location. Around the bases inside the villages we put banners demanding them to leave but the soldiers throw them into the river. One time we called the human rights organizations, and reported the army. At the end, the Colonel ordered the soldiers go down to the River to collect the banners and put them back in place. —Secue was smiling— we had our moment of laugh watching the soldiers repositioning our banners. We were the resistance. We rejected the war and defended the peace.

María Elena Toro, 68-year-old, with a yellow flower between the ear and white hair, had enormous experience deploying banners. She has been doing it for fourteen years. Every Wednesday she was parading in circles in front of the Church of la Candelaria, in the center of Medellin. When Don Berna, one of the biggest drug traffickers and paramilitary leaders, was imprisoned, she wrote him a letter demanding him to tell her where they took her five missing relatives. She then visited him in jail to look him in the eye and wait for the response. Don Berna gave her some hints. She found the remains of her sister, her brother-in-law and her nephew in a common grave; leaving her with her son and his friend missing. Maria Elena always fights the big battles, and never quits. Now she asks the government for more researchers and excavators.

—I hope they put as much effort as with the tower bodies —she says.

On October 12, 2013, a 24-storey building collapsed in Medellin leaving eleven people dead. The last three corpses appeared two weeks later, after a nonstop work in which participated 110 workers, four bulldozers and 25 trucks, removing thousands of tons of concrete.

A few kilometers from there, dozens of bodies remain buried beneath the ashes of the Comuna 13. Overnight the paramilitary threw there the bodies of their victims and by day the trucks threw more layers of debris. Don Berna said that there could be found around three hundred dead. Trucks are still throwing materials and at some points the dump has now reached a depth of fifty meters. Some authorities even suggested declaring the dump, a cemetery.

—If only the dead were from a rich neighborhood, or were relatives of politicians…

María Elena spends the afternoon making a doll in the Park of the life in Medellin, accompanied by other twenty-six women. The dolls represent their missing or killed relatives, and dress them with clothes that they wore when they were murdered or kidnapped. It was not an unusual scene to see a mother dressing a doll with a broken part of children’s pyjamas.

The first doll they make is a tough test for everyone.

—What the hell do I do putting my son’s clothes on a doll, instead of putting them on him… —says almost crying María Lucely Durango— mother of 17 years old boy who was killed for crossing one of the invisible lines between gangs in Medellín.

They sew, doll by doll, creating a memory, something to remind them. One of them, called Marta Lucía Betancur, a retired University Professor, expert on restorative justice, helped building the park of “Sueño de los Justos”, in collaboration with the city of Medellin. One of the women dreamed that her missing son called her from the depths of the forest. So the Park will have a forest of memory, in which each woman planted a tree in memory of their missing and loved ones.

Rosalba Usma told us how they killed her three brothers, husband and daughter, who got out of bed in pyjamas woken up by the screams.

Karen García remembers when she lived in the countryside rebels tied up a friend of hers to a horse and started dragging him until he was dead, and when she moved to the city the paramilitary tied another friend of hers to a car and dragged him to death. Other women speak of recruited sons, missing daughters, children thrown into the dump in Medellín.

With some of those testimonials, the air in the room was as tight as a drum skin, until the tension started to hurt so much and they all burst out crying. The most tranquile women rose to embrace and kiss their friends.

We are tough women, they say, we help each other. We find relief in the company of the group, understanding, and helping. Some of us have met with the killers in prison and have managed to forgive and recover a little peace. Others insist on that the reason they live now is to give love to those who need it: take care of surviving children left orphaned or crippled or other mothers who need their help. Others find peace in faith.

But there are some that do not find consolation, nor strength, nor hope. In Colombia victims are powerful people: active, strong in the defense of their rights and the demands to power, with creative projects. Their motto is “We are not victims, we are survivors”. But it is not enough to say it. This transformation is very demanding and not everyone can follow it.

Luisa, one of the women weaving dolls, and who prefers to hide her real name, saw the murder of her son 20 years ago. She left her husband because of the everyday beating she received from him. Now she lives in the big city selling pies on the street. Three months ago her daughter disappeared. She was barely 18.

—To me this reconciliation looks like some twisted kind of farce. They are held prisoners, say they regret everything and then are cut loose. I don’t believe in forgiveness. My live is an illness. I take medications just to survive, a lot of days I cannot even get out of bed. The state does not help me in anything. It seems that I do not exist. I’m completely alone. For me the death would be a relief.

Carlos Beristáin, psychologist and an expert from the Inter-American Commission on human rights, explains: «When there is justice, truth and reparation, people start to leave behind the painful past and learns to live again. But if those conditions are not met, people cannot move away from that traumatic past or look forward. They are stuck in the past going in circles».

Paula Gaviria works on the 32th floor of one of the tallest skyscrapers in Bogota. The windows in her office provide a spectacular view of the city, spread over a plateau almost 2,600 meters above sea level. In her memory she has one number: 5.845.002.

It is the number of people registered, in a unit called “Unit for the Comprehensive Attention and Reparation of Victims”. It is almost 12,5 % of the population or in other words one in every eight. Gaviria, a lawyer specialized in human rights, 40-years old, was chosen as Director of the unit in 2012, by consensus made by the political parties and civil associations.

—I understand that many people feel abandoned —she says—. It is very difficult to ask for patience, but we started to work just a year ago. We’ve created a record of the victims and we are already providing service to thousands. It is not about sending them just a check. We are trying to repair their lives as complete as possible. It is slower but it is fair.

The Colombian Victims’ law is one of the most ambitious and complex ever created. There was a first attempt to pass it in 2009 but the Government of Álvaro Uribe rejected it because of the cost and because he refused to admit the State responsibility, even in violation of human rights. In 2011, the Government of Juan Manuel Santos and a large consensus passed the law. They established the unit, armored finance for ten years (about 21.000 million euros) funding a reparation for almost five million victims, who were already almost six, because the conflict was still an open water tap.

The first is the recognition, says Gaviria. The State sends a letter to each victim, which acknowledges that it was not on their side and is committed to support them through the healing process. Then came economic compensation, physical rehabilitation and psychosocial programs, restitution of lands, rebuilding destroyed communities, acts of memory, symbolic reparations… So far, the unit has helped 230,000 victims, of which 200,000 received individualized counseling to reorganize their life projects.

Next to the glass office of Gaviria passes a group of women wearing bright colors, flowers, head scarves and large necklaces. They are Wayuu, women from the Bahía Portete massacre. On 18th of April 2004, dozens of paramilitary arrived in the village and murdered one by one the indigenous leaders opposed to their presence in the area, where were the routes of the drug trafficking. They tortured, raped, dismembered and killed six people —almost all of them were women leaders— and left the village totally destroyed: its inhabitants fled, many of them to Venezuela. On the walls of the houses the paramilitary painted images of raped women, torn out breasts and slit bellies. Nine years later, only five families still live in the village and somebody repaints the images quite often.

The Wayuu women now have come to Bogota, to the unit, because after receiving emergency aid, they are now planning the safe return and the reconstruction of their home village.

—Obviously we have a lot of work to do, but for now it is going well —says Gaviria.

The repair progresses, but the injustice remains. The International Criminal Court keeps Colombia on the list of “observed countries”, because of the war crimes and crimes against humanity that have been committed on a large scale with so few trials. There is almost total injustice in the cases of sexual violence against women, as it is explained in a report from the United Nations Commission in October 2013: nobody investigates nor protects or accompanies the victims. They are subjected to enormous pressure from the authorities, to make peace with their aggressors.

The Green Party Congresswoman Ángela Robledo was having breakfast on a balcony over the streets of Bogota, while reviewing the newspapers happily: yesterday, 23 October 2013, was a great day for the fight against impunity, she said. The Constitutional Court rejected the expansion of the military criminal jurisdiction. A resolution made by the Government of Santos, leaving soldiers in the hands of military courts. According to Robledo, this was only an escape route.

She often clashes with the military. Together with Ivan Cepeda (An Alternative Democrat), prepared a draft law against the sexual violence. They obtained the support of many congressmen, even from the Government itself, and surpassed several parliamentary debates.

—But at the last moment, when the law came to the Senate, the Minister of Defense, Juan Carlos Pinzón, pressured several senators so that they stop the project. There are several things in our law system that the military do not like. The Constitutional Court recognized that sexual violence is systematic within the conflict: that is why wewant it to be listed as a crime against humanity. We are also negotiating with the Ministry of Defense: demanding to create a protocol to punish sexual violence, because the military commit many and no action is taken. And we need to train employees, create a facility where people who want to help can receive training. It is frequent that police, judges and prosecutors question and blame the victim. The ask how she was dressed, why she was out so late, they treated her as an immature person and force her to repeat again and again the painful story. Many of those women leave the allegations because the process is too humiliating.

Someone was knocking on the door at eight o’clock in the evening, on August 7, 1999. Enrique an 11 years old kid was watching cartoons on television. His parents were not home: they had gone to spend the day in the city, shopping, and had not yet returned to their coffee farm “La Confianza”, in the valley of “Cauca”. His 20-year-old sister didn’t respond. They knocked on the door again and Enrique rose from the sofa. He opened the door and saw twelve or fifteen armed men. They were wearing armbands with the letters AUC: “Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia” the paramilitary organization that murdered thousands of people between 1996 and 2006, with a special taste for torture, beheadings, chainsaw dismemberment and use of poisonous snakes. The AUC, funded by large industrial and livestock companies, were dedicated to the theft, extortion and drug trafficking. Seven days before Enrique opened the door, the men of the same unit of the AUC arose in front of five hundred peasants celebrating in the nearby village of La Moralia, announced their arrival in the valley, made clear their intentions to punish those who had relations with the guerrillas. Took a 45-year-old farmer and his daughter of 18 and shot them in the head. During the next five years over eight hundred people were murdered in the region and all of them buried in common graves.

—Your family name? —was asking one of the soldiers holding a piece of paper.

—Gálvez Flórez.

The man looked at the surnames in the sheet and did not find them.

—There is no problem with you. —He told Enrique—, but we come here to stay.

Over the next few days the paramilitary settled in the farm. Arrived dozens of men, trucks, weapons, set up guard posts, commanders occupied the house and had the little Enrique as a servant. His parents took their daughter to the city, to keep her safe.

The paramilitary were interested in the strategic location of the farm, because it was on the road to the village of Pardo Alto, where their main base was established. They patrolled the area, arrested peasants and carried them to the farm, where Enrique could see how they tortured them.

About three months after the occupation of the farm, one of the paramilitaries ordered Enrique to bring him a jar of water to his guard post. He was a very dark-skinned and short man. He was called Guerrillo, because he had been in the People’s Liberation Army before getting inside the paramilitary. When Enrique brought him the water, Guerrillo put the tip of his AK-47 rifle on the face of the child.

It took Enrique twelve years to tell what Guerrillo did to him on that day in November 1999. From this point his behavior changed completely, from excellent and always smiling student to dark and aggressive. He tried to commit suicide on several occasions. Now, at the age of 26, he is about to finish Political Science degree still asking for anonymity.

—I remember with great detail the gun barrel pointed at my head. I could see the whole rifle behind it. I froze. Guerrillo grabbed me and took me to a shed. Told me that if I scream he will kill me, and after that he raped me. That is how my life broke into pieces. I felt ashamed, and dirty. I was just a child. I thought I was useless, that I was not a human anymore. I washed my body around 12 times with some kind of detergent that left white spots all over me. I found venom in the farm and tried to end my life two times. I was desperate.

Enrique did not say anything to anybody. In the records of the Victims Unit, 18% of those who suffered violations were men. This is a very heavy stigma which doesn’t let them report.

—I didn’t tell my parents and became very lonely and very aggressive. A lot of times had bursts of weeping. I could not concentrate on anything and failed all of the school exams. My parents thought I was taking drugs and punished me. I tried to kill myself several times, taking pills.

Two things saved him. One was the reading. He began to read everything that could find about psychology, traumas, the Colombian conflict and written by Thomas Mann, García Márquez and Vargas Llosa. He said reading had liberated him to go out and see the world. The other thing was the Victim’s Law. When it was approved, he saw a possibility of shelter and for the first time he told his story to someone.

—The morning of July 19, 2012 was very cold. I came trembling to the legal department and told my story to the officer. I was afraid that she would despise or mock me, but instead she listened respectfully. I went out to the street and felt lighter, free for the first time in my life.

Enrique Gálvez was included in the registry and started to receive psychological treatment.

—Slowly I began to forgive. I don’t know anything about my assailant, if he is alive or dead, free or imprisoned, but in reality I didn’t care. I forgave myself. I stopped feeling that grudge from inside and started to create my own projects. I restarted my Political Science Study I had left years ago, because in Colombia you have to go deeper, and I want to fight for a fair society. The laws work: they saved my life. Now I study and have a girlfriend, which until recently it was impossible for me. Recently I bought a bike to explore the mountains. I want to travel by bike around Colombia, Brazil, Perú and Bolivia…

The victims look like they are awkward people; inactive, unresisting, dedicated to ask for help, but it is just the opposite: they are people who fight because they want to return to society. The violence drove them away from the society and now they want to be a part of it again.

—I had to choose between being a victim and being a journalist, and I decided to be a journalist —says 39-year-old, Jineth Bedoya, subeditor of the newspaper El Tiempo. So in 2009 she encouraged herself to tell her story. A story kept in silence for nine years and for the first time told in a program on the national television.

Back in 2000, Bedoya was a 26-year-old journalist investigating arms trafficking between State agents and paramilitary groups. One day she visited the “La Modelo” prison, called by an imprisoned paramilitary leader who promised her statements, and she went there with another journalist and a photographer. She separated from them just for a moment while they were arranging the paperwork to enter, and three armed men seized her and took her into a car. For sixteen hours they raped her, tortured her and at the end left her in a dumping site.

Bedoya’s life was shattered to pieces. She suffered very serious physical and mental attacks. But she at the end found a reason to live: journalism. He continued with her research, even after she was kidnapped in August 2003 by Farc, when preparing a report about a village where members of guerrillas forced the residents to produce cocaine. But she didn’t tell her full story up until 2009, when Oxfam Intermón organized the campaign «Take my body out of the war».

—Violence against women is disturbing and nobody wants to talk about it. For this reason I was encouraged myself to put my face on the campaign.

Since then Bedoya doubled her work. On one hand, she insisted on the journalism: publishing books and articles on leaders of the Farc, on paramilitary leaders organizing patterns of child prostitution and drug traffickers. From one hand she confronts Mayors, prosecutors and Ministers not particularly happy with her work. On the other hand, organizes campaigns with the slogan ‘It is not time to shut up’. She managed to convince famous football players to send messages in stadiums against violence, staged concerts and festivals and gave speaking sessions to journalists.

Jineth Bedoya sleeps three hours a day.

She has health problem and receives death threats almost every day.

She also received international awards but rejects invitations to spend one or two years in foreign universities. She prefers to die fighting in Colombia, than from depression in a hotel in Europe.

Jineth Bedoya is a not very tall slim woman with a fragile smile, almost always accompanied by her enormous bodyguards and moving around in an armored vehicle.

—It sounds dramatic —she says, with mild and somehow strong voice—. I feel that I live in a race against time. I don’t know how long they will let me live. That is the reason why I do so many things at once. I have no personal life, not because I can’t, but because I need all the time to keep working.

Ana Secué, the woman who was Governor three times shares the same faith with Jineth. She was named governor after the most violent Farc attack upon the indigenous peoples of Cauca.

—My colleagues thought that putting a woman on top of everything would be a good strategy. That would distract the guerrillas. I had been working in the community for years, but the men did not agree to put a woman as a leader. Our community was always a sexist place. Some were angry when I became Governor. It was a shame for them. At the Assembly I made it very clear: ‘I know that the guerrillas will kill me eventually. Here I am, not hiding’ . After that I went home and cried, cried out of nerves, fear, and responsibility. But I only cried in my house. In front of the men I was always very hard, very strong, no place for weakness. And when I was Governor another thing happened to me. My husband was always beating me. I was 15 and pregnant when he hit me for the first time. I had five children with him. He was forcing me to stay home, didn’t want me to go to the conventions. My children encouraged me and I left him. Not until I was Governor, though. It was ridiculous. I was the one who encouraged all of those women to look for the justice and defend their rights and in my own house I was the one who got beaten. So one day I told myself: no more. And told my husband: Don’t you dare hit me again, because the next time you come home drunk I will hit you.

Ana smiled, showing a small replica of the cane tied on her bag.

—And he never did.

Photograph: Pablo Tosco (Full gallery here)

The article was translated by Boyan Aleksandrov

Oxfam Intermón supports women and Colombian organizations in their struggle to report sexual violence in the armed conflict and demand justice. If you want more information, click here

Pingback: Bitacoras.com

Pingback: La nadadora entre los tigres