Report made with the support of Intermón Oxfam

In the community of Aguascalientes, in the Polochic Valley, an idyllic place northeast of the capital of Guatemala, roosters wander aimlessly and crow at the wrong time with harsh voices. They must feel the sadness of the people, campesinos (peasant farmers) forced off their lands in March 2011 by the company Chabil Utzaj (The Good Harvest). They are Q’eqchi’ Maya; evicted from the land where they planted corn, beans, chili peppers, and cardamom. For them, the ex-dictator José Effraín Ríos Montt and the absolute power he represents is not a distant past, but a continuous present.

Enrique Quibb shows the five bullets he picked up from the ground during the takeover of Aguascalientes. His hand is firm but his voice breaks with emotion. He speaks of armed soldiers, violence, trucks hauling people away like cattle, stolen lands, and humiliation. It is hard for him to keep back the tears.

Juancho Chokool is missing his right leg. In the shade of a tree he listens to Quib’s story, leaning on his crossed crutches. His mouth, half-open, is frozen in an expression of anger. Juancho is a sailor, in charge of navigating the Polochic River in a wooden canoe that has leaks in every corner. The campesinos want to show the destruction caused by Chabil Utzaj, owned by the Nicaraguan multinational Grupo Pellas.

They describe how on the other side of the river heavy equipment razed their crops of corn, beans, and chili peppers just two weeks before the harvest. Although the land belongs to the company, Guatemalan law states that the first one hundred meters of the river bank are public land. No one reports Pellas to the authorities. No one believes anything will be done in a country without a land registry or rural courts and where 97% of homicides are left unpunished.

The landscape is beautiful with the Sierra de las Minas Mountains in the distance, the objective of concessions of eager mining companies. Some people cross the river on foot in a shallow zone. The water comes up to their waist; they raise their arms in the air like prisoners. Candelaria points at some land that has been dug up. “What do they get from taking our food? What harm have we done? Why don’t they just let us live?”. Shortly after a small red plane owned by the company takes off. It flies around in low intimidating circles. Its purpose is to frighten off invaders, what they call the evicted farmers who resist giving up their land. A shot is heard in the distance, the echo of the valley returns another shot.

Guatemala is proud of its Mayan culture. It shows it off. It is the image, the fingerprint of a nation with a population that is a majority indigenous, between 50 to 60%. It seems to be a friendly place to the one million eight hundred thousand tourists who visit each year, leaving around 1,300 million dollars in Guatemala’s economy. This, and the money sent by emigrants (4,800 million, 10% of the GDP), is one of the main sources of income. The ancient Maya, their millennial culture, the pyramids of Tikal, are Guatemala’s claim to fame. Today’s Maya of Polochic are never featured in the catalogs of travel agencies or billboards in airports. They are invisible to tourism.

Inside the beautiful Guatemala, there lies a rough and violent Guatemala where there are 38 crimes per 100,000 people – only Honduras has more – where shops are protected by iron bars, shop attendants work in fear, and private security (the number of which surpasses that of the police) are armed with old weapons that look more like scraps than security. Guatemala smells like fear, like the lost bullets of Johannesburg.

Inside both, nested like a Russian doll, hides a third Guatemala, one that persists, racist, exerting violent policies against the poor and women every day; one of land owners and multinationals that accumulates riches and takes the most fertile lands (70% of the land is in the hands of 3% of the population); one of the military that remains a separate power 17 years after the signing of the Peace Accord in December 1996. It’s this Guatemala that threatens, stalks, kidnaps, and kills campesino leaders, union leaders, journalists, and defenders of human rights who hold onto a thread of hope.

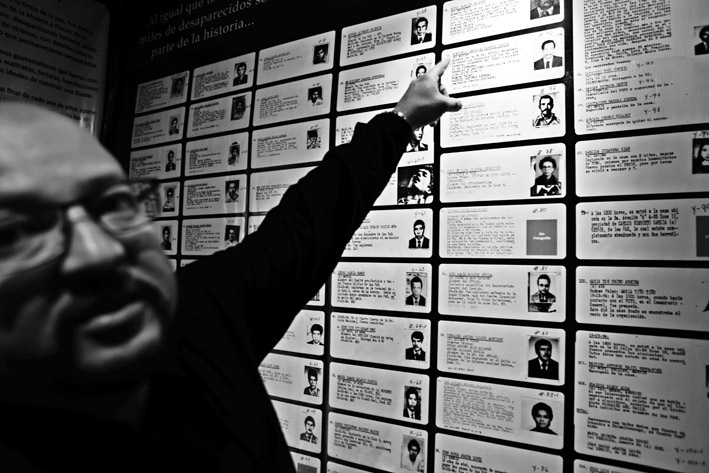

Ríos Montt is the first ex-dictator in his country to be put on trial for genocide. Every morning, in front of the Supreme Court near a plaza called the Square of Human Rights, a colorful line of silent people forms. They are Maya Ixilies: mothers, fathers, wives, husbands, brothers, sisters, and relatives of the victims of the massacres that took place from March 1981 to August 1983 under orders from the government of the general who is on trial: 1,771 dead, 1,465 raped minors, 29,000 displaced families in the Ixil triangle (north Quiché).

“We never thought we would get this far,” says Alejandra Castillo, assistant director of the Center for Human Rights Legal Action (CLAHC), who is responsible for advising the relatives of victims. “We have been fighting for 12 years. For the first time, we are hearing the stories of the people who suffered genocide”. Castillo speaks with emotion that fills her with electricity, seated on a sofa near the courtroom. It’s eight o’clock in the morning. The elevator doors of the third floor open and Ríos Montt emerges surrounded by a crowd of bodyguards. At 86 he looks tired. Little remains of the military strongman who in 1982 threatened to execute his enemies. As he passes the sofa, the ex-dictator nods his head. Castillo doesn’t respond to the gesture as she makes her way to the defendant’s bench.

The leader of the fight for the defense of indigenous lands is Daniel Pascual. He is the general coordinator of the Committee for Campesino Unity (CUC). He is forty one years old, tall, has thick dark hair and bright eyes. He wears a red poncho and a timeless straw hat. CUC has organized an event in the center of the capital to remember the evictions in Polochic that started two years before and to highlight the unfulfilled promises of the president, ex-general Otto Pérez Molina, who promised to give the people land. People on the street stop and observe curiously for a few minutes before continuing on their way. The law of silence remains like a collective stain on the country in which 25% of crimes against human rights defenders are committed by the State.

Pascual maintains that Guatemala’s land conflict is historic: “It started with the invaders who colonized our land 520 years ago and it became worse at the end of the 19th century with the redistribution of lands ordered by president Rufino Barrios”, he explains. That liberal repayment affected the privileges and the property of the church, but not the landowners, and it never benefited the peasant farmers, whom Barrios converted into forced workers on State farms.

Threats don’t frighten the leader of CUC. His goal is to define a common platform for the campesino’s demands that will put pressure on those in power and create real and sustainable change. In March 2012, CUC organized the Indigenous, Peasant, and Popular March in the capital. The march travelled 212 kilometers on foot. No one had given a second though to the cause until thousands of people came together in the demonstration. The capital gave them a hero’s welcome and forced the authorities to dialogue and consider their demands. There were meetings with the Government, Supreme Court, and Attorney General. Promises rained down. Later, when they were out of the limelight, promises were left unfulfilled and bureaucracy returned. The impact of the protest diminished, like the peace accord.

Pascual complains of a permanent climate of impunity and of corruption which affects, among others, the institute founded in 1999, Fondo de Tierra (Fontierra). What should have been an instrument for the process of reconciliation has ultimately become a disaster. Lands were bought for the relocation of peasant farmers who were evicted during the civil war. The farmers paid with “seed capital” and credits which they can no longer pay. It was the idea of the World Bank; an experiment called ‘market land access’. As a result, the farmers’ debt rose to 331 quetzals (33.2 million euros).

The farms that were bought had a 10 year grace period which, in the majority of cases, has already expired. Fontierra wants to cancel the mortgages and take away the land. The campesino march called for President Pérez Molina to cancel this debt. Many communities believed they would be forgiven as compensation for what they had lost during the conflict. There were also third party sales, negotiations, bribes, ignorance, and illiteracy. Although the government promised a solution, collective bargaining doesn’t exist, and each case is being ruled individually.

Jacobo Árbenz was the only Guatemalan president who tried to create real agrarian reforms. He was overthrown by a coup d’état in 1952 organized by the United States from Honduras under the excuse of communisim. Those were the days of the Cold War. In danger, among others, was the United Fruit Company, whose unsurpassed power in Central America gave birth to the term banana republic. Its influence was such in Guatemala that the only railway in the country was constructed to transport products from the plantations to Puerto Barrios on the Atlantic. The end of Árbenz was the end of a decade of democracy, the only window of freedom in hundreds of years of barbarity. In 1960, civil war exploded (the internal conflict, according to military terminology). It lasted 36 years: 200,000 dead, between 40,000-45,000 missing; a sick and broken society which lost its understanding of honesty.

The killings coincided with the land disputes. The military joined the landowners, becoming another predatory class. “What is happening today in Polochic Valley,” Pascual states, “is the continuation of a process. Many of the lands taken in the conflicts were sold to their current owners. They are lands that belonged to the great-grandfathers, grandfathers, and fathers of the campesino farmers who work them today”.

Land ownership is the biggest threat to the Peace Accord of 1996. This is recognized by the High Commissioner of the United Nations in Guatemala, Alberto Brunori, an Italian who has spent 12 years, on and off, in in the country. He is an expert who must speak diplomatically, discreetly. One of the pillars of the peace accord should have been the Integrated Rural Development law, destined to promote “the democratization of the agrarian structure and discourage land concentration”. The law hasn’t been approved and it isn’t expected to happen in the coming months. Although they usually don’t get involved in such delicate topics, business owners consider the law to be expropriation. Parliament, dominated by the economic elite and the military, blocks every effort for land reform, a taboo topic. Despite the growing difficulties, Brunori says that “it is excessive to say that the peace treaties have lost their weight”. Some peasants favor the idea of a return to armed conflict, but there are no arms, no money, no desire, no impulse; only an exhausted society in which a strong extreme right military threatens a coup d’état if the State condemns one of theirs.

Added to the traditional land disputes is mining. Multinationals are knocking on the Government’s door eager to exploit the natural riches. Transparency doesn’t exist in such concessions. President Alfonso Portillo, part of Ríos Montt’s party, awaits trail to be extradited to the US for money laundering. His administration was the most corrupt of the corrupt. On the third day of his hearing, dozens of day laborers suddenly appeared seated near the Minister of Finance, ironically, to show their support for Portillo. Why have you come here, ma’am?, a journalist asks. “I believe something about Portillo, but I’m not sure what,” the woman responds. Where have you come from? “The bus station”. It was a good day of work for the ‘supporters’ of Portillo: 100 quetzals (10 euros), food and transportation.

At Los Alpes farm, located between the clouds and the mountains in the region of Alta Verapaz, the air is filled with worry and fear. Two hundred and seventy-three families are faced with the imminent eviction from the lands of their ancestors. They don’t have schools or wells. The nearest medical center is in La Tinta, a 45 minute journey by SUV. They are very poor farmers who can barely live off their traditional crops. Marcelino Chen is the oldest. He still walks tall despite his 88 years. Pride and a deep feeling of belonging keep him going. His hands are strong, with veins and lines like the grains of an oak tree. “I’ve worked this land with these hands for 68 years”, he says. He doesn’t receive insurance, a pension, or appreciation.

Clotilde is a mother of eight. She also watches with a restless look, a mix of defiance and sadness. She’s just spoken in the assembly, informing the others of the news of the struggle and the need to unite with CUC to defend their rights. The men respect her words that are charged with resistance, which says a lot in a society that is still profoundly sexist.

The campesinos of Los Alpes claim to be the owners of the land that they live and work on, but they lack the legal documents to prove it. The majority are descendants of mozos-colonos, people who were tied to the land even if the ownership changed hands. Some landowners paid them; others let them harvest subsistence crops in exchange for their slave-like work. The minimum salary in Guatemala is 2,421 quetzals a month (242 euros). Pascual says it ought to be called the maximum salary; almost no one receives even that much. Sugar cane workers earn one dollar per ton of sugar cane. Only the strongest and the youngest can do the job. It’s hard work, at thirty you are considered old.

The owner of Los Alpes died in a plane accident. He left 34 million dollars of debt and some orphaned workers. ‘Señor Hans’ (he was of German origin, like many landowners in the area) must not have been very popular because his death was celebrated like a blessing from the gods. The man who wants to buy Los Alpes will only take a ‘clean’ farm, with no workers. The trend in the valley is to plant African oil palms and sugar cane. Landowners are dedicated to the production of raw vegetable material for bio combustibles.

The campesinos call the land that feeds and protects them Pacha Mama (Mother Earth in Quechua); it is the center of their culture and cosmology. Despite being half of the country’s population they lack political weight. Their rejection of ladinas (white and mestizo) institutions and their linguistic division (there are 22 Mayan languages; the majority of which are not mutually understood) leave them outside of the system.

“The main difference with El Salvador is that they don’t have the indigenous question”, claims a source who has spent 40 years in Central America, but prefers not to be identified. “In El Salvador peace agreements work because the guerillas were strong and assured equality in the institutions they created. With peace they gained political power. In Guatemala, the guerillas focused their efforts on achieving extraordinary peace treaties on paper, but afterwards they were excluded from any real power”.

“For the indigenous people, corn is not only food, but it is their connection to the land, a religious commitment,” explains Enrique Naveda, editor-in-chief of Plaza Pública, an informational website that is a breath of fresh air in the print and television panorama controlled by the biggest fortunes. He mentions Miguel Ángel Asturias’ masterpiece, Men of Maize. “ They are accused of blocking progress, of opposing mining and mono-culture farming of sugar cane and African oil palm, but for them progress is that the mountain continues to stand. It is a different life, a different way of thinking”.

Jot Down tried repeatedly to interview the Minister of Agriculture, Elmer López. Due to his schedule the constantly postponed meeting was never possible. He also did not respond to the questionnaire sent to him by email.

The community of Los Alpes doesn’t trust the government of president Otto Pérez Molina. Their leader, Santiago Rax, claims that the government tries to give them worthless land. “We are worried. We know what has happened on other farms, we know how evictions happen”. Father Darío Caal is a small man; he is 56 and full of energy. Seventy-four communities depend on him; he listens, helps, and leads mass to the best of his abilities. He brings hope to Los Alpes, the closest of his communities. “I visit the people that are far away once or twice a year. My parish extends between two mountains,” he says pointing to the Las Minas Mountain on the other side of the Polochic Valley. “The only globalization that has reached us is the cell phone and Coca-Cola,” he laughs. Father Darío also receives threatening messages and letters that accuse him of inciting violence. In one letter he is accused of the ‘crime’ of organizing people through the Internet.

After descending a rocky road that starts in Los Alpes, arriving in the town of La Tinta in the middle of the valley, graffiti welcomes the visitor: ‘Long Live Zapata!’ ‘Politicians are Bullshit!’. The state evicts ‘illegal’ peasants from the land where many of their ancestors are buried, and the state buys the land from those with documentation in nonrefundable deals. Another Guatemalan, who also prefers to remain anonymous, explains the method, “You’d better sell it to me now, if not I’ll come back to negotiate with your widow”. The threats are no laughing matter in a country where violence and politics go hand in hand.

Crossing the Polochic River and wading across two more rivers brings you to La Constanza, a community surrounded by hule (Nahuatl for rubber) trees. The light of day hardly breaks through the forest. It is as silent as a cathedral. Every tree is marked with spiral cuts that are used to collect sap. The people live in poverty, in shacks rented to them by other peasants. They pay 150 quetzals a month (15 euros). The men sell wood for 10 quetzals a day (one euro) in La Tinta and in Telemán, two of the biggest towns; the woman wash clothes in the river for 15 (one euro and fifty cents).

The story of Olga Chu is the story of her people: dozens of soldiers and police, guns, violence, shouting, insults, burned clothes and houses; evicted with nothing but the clothes on their backs. At the other end of a shack that serves as a meeting center there is a table converted into a makeshift altar displaying the CUC flag and a lit candle. At her side, a young mother is feeding her baby. Her mouth is dry, speechless; she listens and smiles without speaking. Each family in La Constanza organizes its existence, work and a means of making money. There is no community leader who assigns jobs. Everyone belongs to the Tinajas farm which is dedicated to the wholesale cultivation of sugar cane. They describe a happy time in the past when they plowed their own land and grew their food. “We couldn’t have imagined what was going to happen”, says Chu.

Mari Paz Gallardo works for the Guatemalan Human Rights Commission (Udefegua), which receives funding from the UN, the US, and Holland, to name just a few. She has endless work in a country where national and international organizations that defend human rights are considered the enemy by the president, ex-general, Pérez Molina’s party. The language is the same as during the civil war, but the package, the patina of democracy to attract investors, is different.

The NGO, Intermón Oxfam, with decades of experience in Guatemala, today studies how to restart a program from twenty years ago that protects human rights leaders, unions, and campesinos. It is a measure of the setbacks.

Where massive violations of human rights have occurred, it is impossible to find justice. The Spanish Judge José Ricardo de Prada, International Judge in the war crimes trials of Bosnia-Herzegovina in Sarajevo from 2005 to 2007, says that “it’s necessary to achieve enough justice so that the victims feel they have been given their due. Because of this, it is essential to judge the leaders, to see that the most powerful don’t remain unpunished. Unfortunately there will always be hundreds who are left unpunished”.

It is important to listen to the victims, to hear what they have to say, like in the trial of Ríos Montt. Mari Paz Gallardo maintains it is necessary, essential, “to return dignity to the dead and the living, and to their families,” something that “has is yet to occur in Guatemala”.

Enrique Naveda, editor-in-chief of Plaza Pública, states that the trial of Ríos Montt “is a military exercise”, no more than a show. Diplomatic sources reject his claim, “It would be dangerous to leave that impression of an Armed Forces trial”. Reports, like Gerardi’s report about the recovery of Historic Memory and the report of the UN’s mission, clearly recognize which of the two sides in the civil war is responsible; the Army and its agents, like the brigades of peasant self-defense, committed 90% of the crimes against human rights.

The Guatemalan media is putting up a battle parallel to the ex-dictator’s trial. The Guatemala Veterans Association is financing pages of publicity that defend their argument that there was no genocide; that past actions, for which there is amnesty, shouldn’t be brought up again. President Otto Pérez Molina, an ex-general who commanded a military unit in Quiché during the era of the dictator on trial, has also shown his support. Everyone is protecting their service records. Everyone is afraid to end up in the seat of the accused.

“Ríos Montt isn’t important. There are many others like him who haven’t been tried”, says a source who has spent 40 years in Central America. Francisco Goldman’s book The Art of Political Murder (Anagrama) is the result of an investigation into the assassination of Bishop Juan Gerardi on April 26th, 1998, where the police and prosecutors on the crime scene were more interested in erasing evidence than finding it, and the later trial.

The death of the prelate happened 48 hours after the bishop’s Office of Human Rights, led by Gerardi, presented the report of the Recovery of Historic Memory, a key document in the reports of military abuse. In his book, Goldman describes the methods used by the intelligence services and the Presidential Cabinet (which Pérez Molina became head of with Ramiro de León Carpio). Their specialty was creating smoke screens, retouching evidence, buying out witnesses, judges, and journalists, and confusing public opinion in such a way that in the end no one knew what had really happened.

San Sebastian church is bustling; dozens of believers come and go wearing their devotion on their faces. One of the priests taking confessions gives a few minutes to the journalist. “The assassination of Gerardi was an important event for everyone, and it continues to be. We really miss him”, he whispers in a low voice so as not to disturb the faithful who pray in the church. “It was a political crime. There is no doubt. He was a man who bothered those in power”. An 82 year old volunteer takes us to the adjoining garage where Gerardi was killed. A photograph of the bishop, a wreath of flowers, and a cross mark where his body fell. On the surrounding walls are murals depicting scenes from his life and reminders of the unending struggle: “No to Mining”, “We just want to be human”, “They were taken alive, we want them back alive”. Inside the garage you can hear the prayers coming from inside San Sebastian church.

Behind the optimistic Guatemala, which is determined to maintain a thread of hope, is the pessimistic nation, which says the country on the verge of becoming a failed state overtaken by drug traffickers. Many of the most recent crimes, including decapitations and dismemberments, carry the mark of the Mexican gang Los Zeta which is working with muderers, who once formed part of the army’s most brutal units, Los Kaibiles, taught by Pérez Molina and charmed by Capitan Byron Lima Oliva, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for the murder of Gerardi. Maras (young gangs), working with Colombian and Mexican cartels, add more trouble to the nations age old conflict. A woman, the Attorney General, Claudia Paz y Paz has become the toughest opponent of drug traffickers and the military. The extreme right hates her, blaming her for the judgments against the military, like the trial of Ríos Montt. Paz is always accompanied by a bodyguard. Pérez Molina has tried to find a way out to get rid of her, but the Attorney General is protected by the UN and the US who commend her work.

Sofía Menchú is a journalist; she is familiar with the Byron Lima case and the way the jails and secret service work. A few days ago she published a report in El Periódico, the most critical newspaper along with the evening paper La Hora, revealing the privileges that captain Lima receives in prison including freedom to come and go as he pleases and control all kinds of business from the inside. She has a bodyguard now. Like the campesino leader Daniel Pascual, Menchú says “we are moving backwards”. “In the first days after the threat I was nervous, I was afraid; but after, I realized I couldn’t continue to live that way, I had to continue my work as if nothing had happened”.

The threats are usually subtle, a telephone call in the middle of the night, a suspicious car parked outside the house; little things that give the message “we know where you live and what you do”. Other times, they don’t bother beating around the bush and take immediate action, like the kidnapping of four union leaders in Jalapa who were preparing a vote that was sure to reject allowing a mining company onto their land. One of the leaders died, two were beaten, and the fourth, Roberto González, miraculously survived. “There were between 15 to 20 men, they wore ski masks, boots, gloves, and had guns. They took the men from their car after following them for a while. They beat them and tied their feet and hands with the tape that is used to hold dynamite. Two men managed to untie themselves and escape with wounds. Robert (the leader from Jalapa) was set free in a hotel 60 kilometers away after we got the attention of the Vice-Minister of the government. I saw him send a message on his cell phone”, explains Juan Jiménez, who forms part of an anti-mining group. Were they hitmen? “No; they were soldiers.”

The problem in Jalapa is the same as in Polochic; land ownership and who has the right to decide how it is used. “We have a Spanish deed, given by Charles V, which states the land is ours”, says Jiménez.

Panzós is a dismal, sad city. You can get there from Telemán, the sugar industry’s favorite town, using a highway that is being constructed. Money from a Japanese Cooperation is paving the dirt roads which were practically impossible to use in the rainy season. The construction workers work hard to complete their job while tractors and large machinery load enormous trucks with sugar cane. The indigenous and the surrounding towns will not be allowed to use the new roads which are being built for the exclusive use of Chabil Utzaj (The Good Harvest). The era of the United Fruit Company continues.

The first massacre of the civil war took place in Panzós in 1978; the first of many to follow in the eighties. Dozens of campesinos were called for a meeting by then mayor, Walter Overdick García. When the people arrived there was no speaker except the Army, who crowded the people into the main square of the town. A woman who led the peasants, Adelina Caal Maquín, confronted the soldier in charge. More than 100 people died, 34 in the square, the rest from their wounds, in the health clinic, being chased in the mountains, or drowned in the Polochic River.

The current mayor of Panzós is Jaime León. He is a member of Pérez Molina’s Patriotic Party. When asked if there was genocide in Guatemala, he says there was. He’s currently involved in a legal battle with the sugar company Chabil Utzaj, trying to impose a municipal tax on the sugar plantation. “We can’t collect any taxes from them because it is as if their crop didn’t exist, there is not paperwork to prove it. The town council needs to approve a law that will authorize a tax. We’ve taken the issue all the way to congress, but at the moment progress has stalled”. Are the companies responsible for blocking the laws they consider detrimental to their business? “They are”, he answers. León says the neighbors complain about the noise of the machines that work 24 hours a day. “We have already convinced the company and three of the most important families in Panzos to construct a detour and a bridge so that the trucks don’t have to pass through the center of town”.

María Maquín‘s home is filled with the same halo of sadness that covers the main square in Panzós. María is 48. She is the granddaughter of Adelina, the leader of the campesinos. The day of the killing, May 29, 1978 she went to Panzós with her grandmother; who was like a mother to her. Covered in blood, she played dead laying with the bodies all around her while the soldiers looked for the living to finish their job. When she had the chance, she escaped to the Polochic River and headed toward the mountains. She was 13 and she knew how to swim. She hid in houses and rocks. The Army went after Mama Maquín’s granddaughter. They didn’t want to leave any witnesses or symbols of the massacre. María speaks slowly, reflecting upon her emotions. Even though she has told the story a thousand times, she still gets emotional when telling it. She says that a priest from Panzós told her about a bishop who wanted to hear her testimony. It was Gerardi, who learned about what had happened when the church was collecting evidence to document the Recovery of Historic Memory.

María Caal Maquín’s son listens to the story as he finishes his homework at a wooden table. Hanging on the wall in another corner of the room are pictures of his heroes: Cristiano Ronaldo, Cannavaro, and Forlán. Maybe they represent a normality that he has never known, or maybe they are just examples of globalization that father Darío, the priest in Los Alpes, forgot to mention, like the Barcelona Football t-shirts that inundate the country.

Many years have passed, but María still avoids going to Panzós. It is a cursed place. The Polochic Valley continues to be a territory of inequality, of land taken from campesinos, of big business. “The Good Harvest?” one man says ironically. “It must be good for them, it is terrible for us”.

Freddy Peccerelli, director and founder of the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation (FAFG), has managed to identify 6,500 missing people with his team of experts. “We don’t work for the dead, we work for the living”, he explains. “When we announced to the press that we had the first DNA bank to identify the missing, we expected that the lines of people would reach the presidential palace, but in the end, no one came. Only after did we realize that making the decision meant tackling a very difficult question; it means ending the search among the living, and beginning a search among the dead”.

“My name is not XX. Your DNA can identify me”, says the slogan of the foundation. XX is a nameless body, a nobody. Peccerelli’s team is one of the best in the world. They’ve worked in Vosoko, Bosnia-Herzegovina identifying the dead of Srebrenica. Guatemala could be the country with the most missing persons per capita. “Not too long ago a reporter from the New York Times was here and he offered an apology for all of the journalists of his country who had paid so little attention to the conflicts in Guatemala. They had all gone to El Salvador and Nicaragua.”

“The Guatemalan Army has been the most violent army in Central America,” a source that has spent more than 40 years in the region says. “When North America stopped sending help in the era of Jimmy Carter, the military looked to Israel and Argentina’s dictatorship instead, neither being precisely the best defender of human rights. It’s hard to admit, but what it reveals is a brutally effective military”. The US isn’t innocent regarding the crimes committed in Guatemala. Bill Clinton asked the victims for forgiveness, but the act of contrition didn’t last long. The next president, George W. Bush, returned to the argument against communism.

Peccerelli says that bones don’t always speak. They don’t always tell the story of how the body that covered them was killed. “The killers here knew how to kill without leaving evidence on the bones”.

The cemetery in La Verbena is a mine of tragedies. More than 3,000 unidentified bodies are buried here. They are the victims of the worst years of repression 1981, 1982, and 1983. “The number was the first thing that caught our attention. Normally, the number of bodies added to the cemetery is not more than 180 per year. The figures are evidence that there may be many of the missing buried here”, asserts Peccerelli. “When we finally do identify the remains and return them to the family it is a very difficult moment. Many families have spent their life searching for the missing person and when they receive the news they don’t know how to live without the search, without their motivation for so many years of fighting. They have to learn to live with the certainty of death”.

Above the door of the foundation hangs a banner with moving words. They are the words of the family of Sergio Saúl Linares Morales, the first missing person identified by the foundation. “Thank you for finding me and identifying me.”

Rebeca Lane is a strong woman, like Candelaria the peasant woman from Polochic who works the land, like the unyielding Claudia Paz. Lane’s weapons are her voice and rap; risky, rebellious, and feminist, her words are like a punch in the face to the sexist and xenophobe society that tries to act as if the past doesn’t exist. In the song ‘Politically Incorrect’, Lane declares that guerilla blood runs through her veins as she reveals that one of her aunts was kidnapped and went missing in the eighties. Her twitter account RebecaLane666 is another weapon in her fight, ‘This is how my land is, and this is how my people are. They kill 200,000 and 45,000 people disappear and they still deny genocide’.

Enrique Naveda, editor-in-chief of Plaza Pública, warns about the Guatemalan trait of extreme pessimism, a result of its Spanish heritage. Yet, despite so much desperation lubricated by years of bloody history, in Guatemala there are still people determined to carry on. Optimists, like Alejandra Castillo, assistant director of CALDH, hope that the trial of Ríos Montt will offer the opportunity to activate the 1996 Peace Accord. Despite the repression, many are no longer afraid: Daniel Pascual, Sofía Menchú, campesinos from Los Alpes like Clotilde and Marcelino Chen, Judge Barrios, María Maquín, the man who showed off the five bullets in Aguascalientes, the sailor Juancho, Panzós’ Mayor León, the men of Jalapa who oppose mining. “I was taught to live in fear, not to speak; but I teach my children to have no fear,” declares the sub-coordinator of the Committee for Campesino Unity, María Josefa Macz. Threats, the dead and the murmur of the unpunished remain, but something is changing inside the Russian doll.

Maybe it’s a matter of patience, a matter of time. The economic crisis and scarce attention from international organisms don’t help. Guatemala has disappeared from the news. Looking the other way shows complicity to the injustice and the killings. Informing, knowing, educating, digging up the dead, judging, asking for forgiveness, and not forgetting is the only way to recover collective dignity, whether it is in Guatemala or in Spain.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Intermón Oxfam has been working with families evicted as Polochic. If you want more information about our work, click here.

Photograph: Ramón Lobo. Edition: Carlos de la Calle.

The article was translated by Dianne M. Conn.

Pingback: Jot Down Cultural Magazine | Guatemala, la transición requisada