Some time ago, being a post-doc in California, I used to take long trips across the USA in my red-arrest-me, not-soeasy-rider Kawasaki Ninja. I went south to Baja and east to the Rockies, north to Washington and all the way up to Montana and then to Utah. I saw a lot of scenery. And I met a lot of people.

One of them was a Navajo indian that I will call Geronimo. He was an old man (probably as old as fifty, a Methuselah for the kid of twenty eight I was then). Geronimo was thin and muscular, dry as the painted desert. He had black, humorous eyes and a degree in Anthropology. During the summer, he earned a living selling pottery and souvenirs.

We sympathized. I spent almost a week in the reservation, hiking during the day and hanging around with him on evenings. We shared reservation typical food (pizza), reservation typical drink (Budweiser) and some medicine herbs that I will not describe here. One of those nights, Geronimo showed me a little portrait that he kept in his caravane, not for sell.

It was called, “Landscape with Apaches”. The art was naive. Simple, clear curves and bright colours. A line describing the horizon. A small rock. A small cactus. Nothing else.

Obviously, what gave sense to the picture were the invisible Apaches. One had to imagine them, impossibly crouched behind the ridiculous little stone, marvelously hidden by the meagre bush. The portrait payed homage to what the Apaches once were, and Geronimo still was, in his own way. The silent people, who could all but vanish in the landscape, who could be the landscape.

Today, the memory of Geronimo and those Apaches comes to my mind, fresh as the morning breeze of those remote summer days of 1988. Here is another portrait, very different from the one he showed me, and at the same time, very much the same.

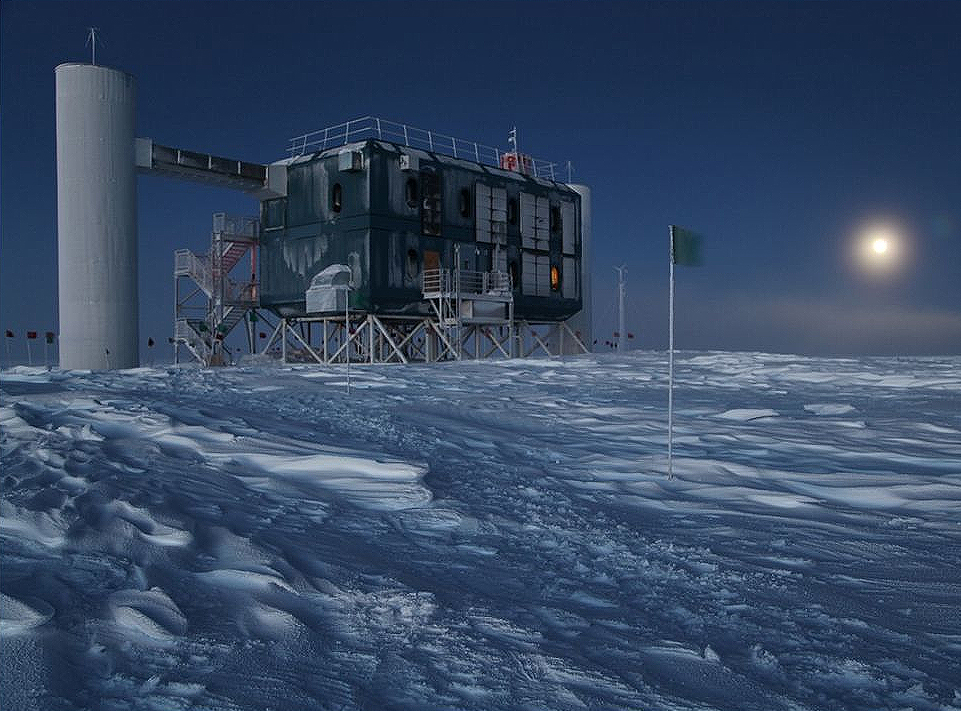

There it is. The photograph shows a building, stocky, metallic, vaguely futuristic. It has a bit of a hangar in it, a bit of a factory. It’s a space ship and also a wreck, marooned in the ocean of ice which surrounds it. Looking carefully, it is possible to distinguish a brush of orange light in one of the lower windows, betraying a spark of life inside it.

The ocean that surrounds the building is the Antarctic plain. We are exactly in the Geographic South Pole, the mythic place discovered by Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott. We are very near the scientific base that carries their names. We are at the very end of the world. Nothing but frozen silence for thousands of miles around us.

The shiny globe in the azure sky is not the sun. Is the moon. It is dark and cold in the South Pole, almost as cold as in Mars. It has been dark for five months and it will still be dark for a few more weeks before dawn breaks a day that will not end in another half a year. During this endless night there are no flights connecting the Amundsen-Scott station with the rest of the world. Even internet connection is limited to a few hours a days, when the satellite passes over the base. There aren’t many folks in the station, either. Just the winter-overs, this strange species, half-monk, half-scientist, mad enough to be willing to spend six months in the coldest night of the Earth, sane enough to live up to the challenge. Geronimo would have been good at this job. The South Pole night has all what he valued. Silence. Time. Beauty. No tourists.

This is the landscape. But where are the neutrinos?

The neutrinos are raining over the South Pole, as they are raining over all Earth. They are produced by trillions in the sun — about hundred billions of them will cross the nail of our thumb every second — but also in the upper shells of the atmosphere, when cosmic rays of great energy hit, luckily, the thick shield of gases that protects and nurtures us. They are also produced by supernovae, those stars who end their lives with an explosion so stupendous as to make them shine as much as the rest of their own galaxy, those fireworks of the Universe that entertain God’s in.nite weariness.

They come from even farther away, messengers of the most violent phenomenon of the galaxy. Those neutrinos of incredibly high energies tell epics too fabulous for our limited knowledge to grasp.

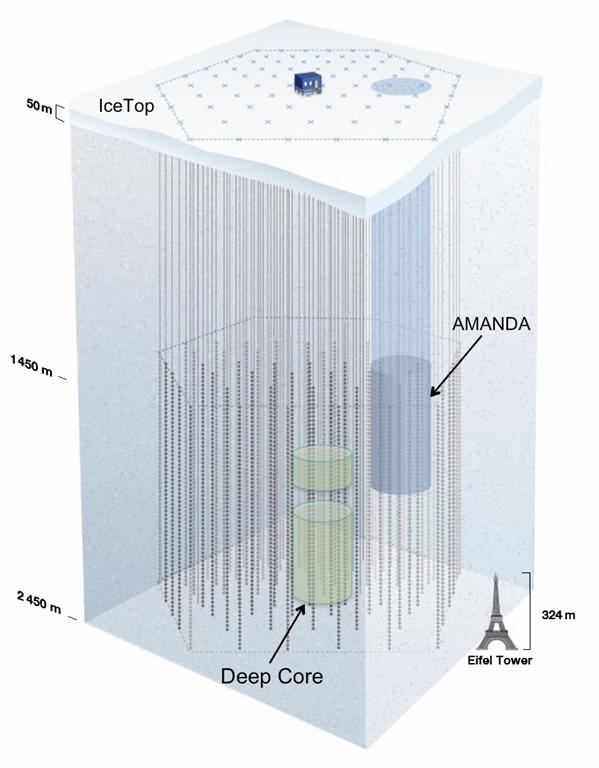

Neutrinos, invisible like the Apaches of my friend Geronimo, rain over and through Antarctica. Below the ice, also invisible to the naked eye, hides the IceCube detector. Imagine an array of eighty six cables, each one kilometre long, buried one and a half kilometres deep in the ice, covering a surface of one kilometre squared. Imagine a big, frozen spider. Her body is a cubic kilometre of ice, her nerves are made of steel, her eyes are large optical modules, 60 per cable. Those eyes can see neutrinos.

It works likes this. One kilometre and a half under the surface of Antarctica, darkness is absolute. The eyes of the giant are open but see nothing. Every now and then, an energetic neutrino crashes against the ice, some times even against the rock sitting two and a half kilometres under the science station. The neutrinos disappear in the collision, replaced by charged particles. Those charged particles move very fast, faster, indeed, than the speed of light in the ice, leaving a trail of blue light in their path. The optical modules can register such light and, using its intensity and timing, deduce the energy and approximate direction of the upcoming neutrino.

Most of the neutrinos that IceCube sees are well behaved citizens. Physicists have been dealing with them for many years, and know that their origin is the collisions of cosmic rays, those high energy particles that wonder the galaxy, most of them protons, survivors of long-forgotten catastrophes. When those derelicts hit the atmosphere, a shower of nuclear fragments is produced. Among the debris, there are particles called pions, which decay to muons (a heavy brother of the electrons) and neutrinos. In turn, the muons will also decay to electrons and more neutrinos. IceCube sees thousands of them each day. Their study was, once, the hottest stuff in the trade. This days, they are mostly background, the unwanted static that may mask the precious signal.

But IceCube has also registered two incredible events, two bombs whose light signature is as large as the centre of Manhattan. They have too much energy to be atmospheric neutrinos, not quite enough to be the messengers of some of the epic events the physicists expect to detect.

What are they, then? What is producing them? What kind of cosmic accelerator is responsible for their fabulous energies? We do not know, but whatever be their origin, we hope it to be far, far away from us.

And thus, the physicist watches her landscape with neutrinos and prays so that God keeps looking elsewhere, far from her green and overheated planet, far from her dear and unattended family, far from her beloved, frozen continent, the last place on Earth, where science, rather than money, rules.

She makes an entry in her diary. It has a strange flavour, an aura of deja vu. She has perhaps read something, very similar, somewhere else, but the words seem to resonate, newer than ever, as she writes.

«Yes, it was right: neutrinos were falling all over Antarctica. They were falling softly upon the great central plane and, farther westwards, softly falling into the white wastes of Vostok lake. They were falling too upon every part of the grave where IceCube lay buried. They crossed the steel cables and the optical modules, in their way to nowhere. His soul swooned slowly as he imagined neutrinos falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of the their last end, upon all the living and the dead».

Pingback: Jot Down Cultural Magazine | Juan José Gómez Cadenas: Paisaje con neutrinos

Pingback: Top 10+ juan jose gomez cadenas twitter hay nhất hiện nay - 2022 The Crescent